Let’s review some basic reasoning: “If it looks like a duck, swims like a duck, and quacks like a duck, then it probably is a duck.”

Greece, the cradle of democracy and western civilization, is in national default. It is unable to pay its debtors. Standard & Poor’s (S&P) has rated Greece’s sovereign debt as junk since April 2010, and the Greek government had to be bailed-out by a €110 billion European Union (EU) and International Monetary Fund (IMF) loan package in May 2010. Despite the loans and some broad ‘austerity’ cuts, the situation did not improve. By June of this year, S&P had downgraded Greece’s debt to the lowest rating in the world.

Last week, leaders of the ‘Eurozone’ monetary alliance and the IMF reached a new agreement to try and alleviate Greece’s sovereign debt crisis. As part of this agreement, many of Greece’s debtors will accept a fifty percent write-off—another one-hundred billion euro gift to Greece. But consider what this means; many banks that bought Greek bonds will get only fifty percent of their investment back. Greece is not able to pay what it owes. We can perform rhetorical back-flips all we want, and fluff it up with as many euphemisms we can come up with (‘Haircut?’ Really?) . . . but when a country can’t pay its debtors the correct word to describe it is default.

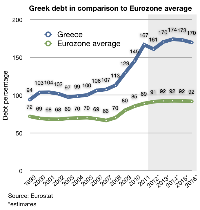

In 2011, Greece’s public debt is expected to rise to over 160 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP). In other words, the Greek government will owe its debtors more than the entire economic production of the country over more than one and a half years. This ratio is expected to rise to something over 175 percent in 2012. It is unclear what impact the default will have on this projection, but it’s stated goal is to reduce Greece’s sovereign debt to 120 percent of GDP by 2020. For the record, a debt-to-GDP ratio of anything approaching one-hundred percent is generally considered to be a crisis. So the most optimistic target for Greece over the rest of this decade is that their crisis will diminish to a slightly smaller crisis. Nobody has yet proposed actually fixing the core problems facing Greece. Like Congress dealing with our own debt crisis, the strategy seems to make a few small tweaks around the edges and call it a day.

The fundamental problem for most of western Europe—and for the United States—is that we have bought bigger governments than we have the means to pay for. The Europeans have gone much further down this road than we have, which is why Greece is already in default and why Ireland, Portugal, and Spain are much closer to it than we are. But in the end, the only way to really solve these sovereign debt crises is for all of us to get our government expenditures in-line with government revenue. Greece did not implement any kind of austerity plan until it was too late, and the plan they finally implemented fell far short of what was really needed.

Nobody seems willing to state the obvious. Nobody seems willing to use some basic reasoning. We simply can’t keep spending more than we make and expect it to magically work out in the end. There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch.