We need to take an honest, dispassionate, rational look back at the War in Iraq.

During George W. Bush’s (R) presidency, no other issue incited the kind of vitriolic rage that Iraq did. It has since become “common knowledge” that our involvement there was, as the Eagles put it in the title track of their 2007 album Long Road Out of Eden, “a bloody stupid waste.” But many of the “facts” people seem to remember about the war aren’t even true. We must untangle the myths and reevaluate our preconceptions.

There’s plenty of room to disagree about whether the Iraq War was justified or right. As long as your opinion isn’t based on the falsehoods described below, I respect it. But at least know what you’re talking about. Don’t believe the mythmakers. Many of the same people and institutions who lied to you about practically everything over the last ten years were lying to you about Iraq a decade earlier too—but not in the way you might think.

It is true that I supported the Iraq war at its inception; you can find plenty of evidence for that on this website. You might accuse me of confirmation bias or cherry-picking evidence to support my preconceived position. I try to avoid that, but I’m not perfect. I have blind spots. Contact me and tell me about them. If you make a good, rational, intelligent argument, and give me permission to use it, I might add it below as a rebuttal.

I hate war. It hurts people. It undermines their rights to life, liberty, and property. I wish it was never necessary, but sometimes it is. We are a fallen, contradictory species. The human right to keep and bear arms, for example, is indispensable because sometimes the use of deadly force is the only way to protect life. War works the same way.

Yet I was never a true “war hawk.” I thought—and still think—that Bush was right to launch the war, but I was already writing biting critiques of some of his war policies all the way back in 2004. When I learned about the abuse of prisoners at the Abu Ghraib prison, I condemned it as loudly as anybody on the anti-war left . . . I thought the perpetrators should have been charged with treason. I unequivocally condemned the use of ‘waterboarding’ torture on enemy combatants. I supported President Barack Obama’s (D) withdrawal plans. You know me; I’m not a blind partisan idealogue.

With all that in mind, here are ten stubborn, pernicious myths about the Iraq War . . . and the truths that lie behind them.

Myth #1: Combatants Were Held Illegally

Critics often claim that the U.S. government violated the provisions of the Third Geneva Convention, the 1920 treaty (revised in 1949) dealing with the treatment of prisoners of war. Others argue that we unconstitutionally denied enemy combatants’ access to the U.S. civilian court system. Both arguments rely on faulty premises.

Part 1, Article 4 (PDF) of the Convention clearly defines who qualifies as a prisoner of war: members of the armed forces of a party to the conflict, or militiamen wearing identifiable insignia, carrying arms openly, and operating in accordance with the “laws and customs of war.” It can also include people in a “non-occupied territory” who spontaneously take up arms to repel an invasion, but only if they “carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war.”

The al-Qaeda terrorists, Islamic State terrorists, and other nonmilitary prisoners captured in Iraq and held (mostly) at a detention facility on the U.S. Navy base in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, do not fall under that definition. They were not members of a military, never wore identifiable insignia, and never carried arms openly. Laying roadside bombs and blowing up churches certainly doesn’t respect “the laws and customs of war” either. We can (and should) object to how the prisoners were sometimes treated, but the Geneva Conventions simply don’t apply.

They had no right right to access U.S. civilian courts either. First of all, they committed their crimes well outside of U.S. civilian jurisdiction. You could argue that Iraq’s civil courts might be an appropriate venue, but even that would be a weak argument. Enemy combatants who commit acts of terror or sabotage off the battlefield are subject to military tribunals. These are well-established under both international law and U.S. court precedent.

The most well-known example of a U.S. military tribunal happened during World War II. Eight German saboteurs were captured in the United States during “Operation Pastorius.” Even though they were arrested on U.S. territory, the U.S. Supreme Court acknowledged that military tribunals, not civil courts, were the proper venue for trying them. “By the law of war, lawful combatants are subject to capture and detention as prisoners of war; unlawful combatants, in addition, are subject to trial and punishment by military tribunals for acts which render their belligerency unlawful” (Ex parte Quirin, 317 U.S. 1 (1942)).

Myth #2: The War Was Endless

As our involvement in Iraq dragged on, those who opposed it complained that it had become an “endless war.” Nonsense.

Bush announced the end of “major combat operations” on May 2, 2003—less than two months after the war had begun. Those operations in the first Gulf War lasted three times longer. The Korean War lasted three years; the Vietnam War lasted eight. We were in World War II for three.

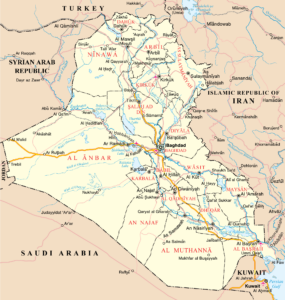

The coalition officially occupied Iraq for just over a year; sovereignty transferred to a new Iraqi government on June 28, 2004. Iraq remained under an “unofficial” occupation for much longer. The last coalition combat troops withdrew on August 18, 2010, and another 50,000 troops remained in noncombat roles until the last of them left on December 18, 2011. Our direct involvement in Iraq’s internal affairs lasted about nine years.

The first Persian Gulf War and the Vietnam War did not have post-war occupations; even so, this “endless” Iraq War lasted only a year longer than Vietnam did. The Korean War lasted three years, but a full, battle-capable American military force of about 23,000 troops is still there today. That’s sixty-six years and counting to Iraq’s nine. World War II poses a similar problem; U.S. forces remain in Germany (about 35,000) and Japan (about 54,000). That’s eighty years (and counting) to Iraq’s nine.

You may protest that the U.S. military forces in Germany, Japan, and Korea aren’t suffering from insurgent attacks or sectarian violence, nor do those countries consider themselves ‘occupied.’ Okay. So let’s compare the length of time from the beginning of a military action to the last U.S. military death due from insurgent or enemy attack, or the formal end the military occupation.

Two U.S. soldiers were killed by North Korean troops along the armistice line in the Axe Murder Incident on August 18, 1976; that’s twenty-six years to Iraq’s nine. There was no significant post-war insurgency in Germany, but the the formal occupation there continued to 1949—seven years to Iraq’s nine. Japan had no insurgency either, but the occupation continued to 1951—tied with Iraq at nine years.

The length of the War in Iraq, however you measure it, was pretty average.

Myth #3: The War Was Unilateral

The U.S. government petitioned the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) to enforce its many resolutions against Iraq, or at least authorize a ‘coalition of the willing’ to do the enforcement for it. Under the U.N. Charter, UNSC resolutions are binding and enforceable with military action. China and Russia used their veto powers to block the effort.

The military force that ended up going into Iraq was indeed dominated by the U.S. military, which constituted about seventy-six percent of the total force. But the other twenty-four percent hailed from six other nations: Australia, Denmark, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom. It also included Iraqi troops from the Kurdish Militia and the Iraqi National Congress.

After the initial invasion, troops joined from Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Estonia, Georgia, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Japan, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Mongolia, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, the Philippines, Romania, Singapore, Slovakia, South Korea, Thailand, Tonga, and Ukraine.

The Iraq War was not a “rogue” action by an American president who thought of himself as a “cowboy.” It was a broadly supported multi-national effort that had the open support of more than forty independent states. It also enjoyed indirect support from others; many of Iraq’s neighbors granted overflight rights, allowed territory to be used for bases, shared military intelligence, and provided other indirect assistance to the coalition, but feigned opposition for political or religious reasons.

Myth #4: There Were No WMDs

Iraq’s “Weapons of Mass Destruction” (WMD) programs were not as broad or advanced as we were told. Supposedly, Iraq continued developing chemical, biological, and nuclear technologies after the first Gulf War, and would soon be able to deploy those weapons against their enemies. That wasn’t true. Were our leaders lying, or just wrong?

There is a truthful answer to the rhetorical question, “Where are the WMD’s?” Lots of them were right where we thought they were: scattered across Iraq in undeclared weapons bunkers.

In 2006, members of the U.S. House Intelligence Committee asked then-Director of National Intelligence John Negroponte (R) to provide a declassified summary of the “key points” of an intelligence report about what had been found in Iraq. The requested summary stated that “approximately 500 weapons munitions” containing “mustard or sarin nerve agent” had been recovered, and that “filled and unfilled pre-Gulf War chemical munitions are assessed to still exist.” Journalist C. J. Chivers later reported in the New York Times that, “From 2004 to 2011, . . . troops repeatedly encountered, and on at least six occasions were wounded by, chemical weapons” and that coalitions forces had “secretly reported finding roughly 5,000 chemical warheads, shells[,] or aviation bombs.”

When the post-war government of Iraq became a signatory of the Chemical Weapons Convention in 2009, it declared two bunkers of chemical weapons and precursors and five chemical weapons production facilities. Numerous prohibited weapons, including including SCUD and Al-Samoud 2 missiles, were fired at coalition troops during the invasion or found during the occupation.

Iraq’s WMD programs were mostly inactive between the wars, but Hussein maintained them in a state of readiness so they could be restarted when international attention faded. The world’s intelligence services misjudged Hussein’s current capabilities, but were right about his future intentions. They were also right when they said Iraq had never fully complied with UNSC resolutions demanding they destroy all chemical weapons in their possession.

All in all, Iraq’s violations were were less severe than we thought. They were still violations.

Myth #5: A War for Oil

Bush was often characterized as a bloodthirsty, greedy tyrant who wanted Iraq’s oil and would stop at nothing to get it. The war itself was often described as a “war for oil.”

Do the facts align with that premise?

A hypothetical “war for oil” would have been focused only on securing the oil fields. Why spend any time, money, or lives on capturing Baghdad and the other cities? None of that would have mattered. If the oil was all the coalition wanted, it could have just . . . taken it. Hussein himself would have been given the opportunity to cooperate or be deposed. Why change a regime that could have been useful in maintaining a brutal, totalitarian order?

As a “war for oil” president, Bush could have contracted the operation of the Iraqi oil fields to connected Texan oil companies, leave domestic staff in place as raw labor, and guarantee cheap gas for U.S. voters who might then be more likely to reelect him. Further troop deployments would be oriented only toward protecting the oil infrastructure. Who cares about internal sectarian violence? Who cares about elections? Who cares about anything other than the oil?

Here in reality, the coalition did secure the oil fields during the invasion . . . because Hussein had a history of lighting them on fire. They were turned over to the new Iraqi government as soon as it existed. Iraq’s oil exports, even under the coalition’s provisional government, complied with OPEC’s supply and price restrictions and were sold through the same cartel channels they had always been. The U.S. government passed-up every opportunity to benefit from Iraq’s oil. It could have manipulated oil prices, given oil to U.S. companies for pennies, withdrawn Iraq from OPEC, and so much more. It didn’t.

There was a brief period early-on when some senators considered using Iraqi oil revenues to reimburse the United States for costs incurred by the war and occupation. It was a reasonable proposal, but Bush rejected it outright. The U.S. government—and the U.S. people—got basically nothing from Iraq’s oil. The way the war and occupation played-out simply doesn’t support the premise; oil was, if anything, a minor concern.

Myth #6: No Justification

Many still claim that the Iraq war as an ‘illegal war’ that had no reasonable justification. Of course, some of them simply oppose all war . . . and by that absurd standard, the myth might be “true.” Here in reality, war can be a regrettable necessity.

Consider the situation as it stood just before the war. UNSC resolution 1441 (2002) passed unanimously in November 2002, and gave Iraq a “final opportunity to comply with its disarmament obligations” under resolutions 660 (1990), 661 (1990), 678 (1990), 686 (1991), 687 (1991), 688 (1991), 707 (1991), 715 (1991), 986 (1995), 1284 (1999), and 1382 (2001). Under the U.N. Charter, UNSC resolutions are binding on all nations and should be enforced, when necessary, with military action. The failure to comply with 1441 was just the “icing on the cake;” Iraq had been courting an invasion for over a decade. If the UNSC just ignores and refuses to enforce its own resolutions, what’s the point of having it?

Iraq could not have been brought into compliance with diplomacy. It failed to comply for twelve years. It was unlikely to comply in another twelve, twenty-four, or forty-eight.

The Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Iraq Resolution of 2002 passed with a broad bipartisan majority: 297-133 in the House (215 Republicans and 82 Democrats in favor) and 77-23 in the Senate (48 Republicans and 29 Democrats in favor). Nearly all prominent Republicans voted for the war, as did notable Senate Democrats in office at the time like Joe Biden (D-DE), Hillary Clinton (D-NY), John Kerry (D-MA), Harry Reid (D-NV), and Joe Lieberman (D-CT). Republicans and Democrats reviewed the facts as they were known at the time and believed that action was warranted and necessary.

Myth #7: American Imperialism

The Iraq War has been labeled as an example of shameless American imperialism . . . but nobody seems willing to explain how. Imperialism isn’t free trade and commerce between nations (no matter what the protectionists and antiglobalists think). Empires subjugate other nation-states and peoples for their benefit. We did no such thing; we gained nothing from access to Iraq’s resources (see “A War For Oil” above).

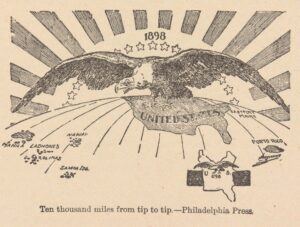

The U.S. flirted with notions of empire at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1898, after the Spanish-American War, we annexed the Philippines, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The Philippines regained its independence in 1946. Puerto Rico regained its right to self-government in 1947, but has freely chosen to remain in the U.S. Only Guam, with a population of only 175,000, remains [technically] a “non-self-governing territory.” We gave up our imperial aspirations a long time ago.

If we had wanted to make Iraq part of a new empire, we could have. We did not have to let the Iraqi people draft their own constitution or put it to a free, open referendum. We did not have to withdraw troops from Iraq on their schedule instead of ours. We did it anyway . . . because we had no desire to make Iraq into a vassal state. We gave the Iraqi people the opportunity to choose their own path, even when it went against our interests (and, frankly, their own). The goal was liberation, not subjugation.

Myth #8: Emboldened Terrorists

Some argue that the War in Iraq emboldened al-Qaeda and other radical Islamist terror groups. This is rooted in a deep, persistent misunderstanding of what Islamists believe and why.

Islamists adhere to a fundamentalist form of the Muslim religion. They seek the establishment of a world-wide caliphate, or Islamic empire, that will convert the whole world to Islam . . . by force if necessary. Those who refuse to abandon their previous faiths will be killed (if they are atheists or pagans) or subjugated as dhimmis (if they are “people of the book,” however the caliphate defines it). Al-Qaeda arose in the 1990s, and the Islamic State in the 2000s, but the fundamentals of their worldview and tactics are as old as Islam itself. They don’t just predate the War in Iraq, they predate the existence of the United States! Hell, they predate the European discovery of the Americas in 1492.

Attempts by Bush and others to link Hussein to the September 11, 2001, terror attacks were misguided and wrong. Hussein did offer condemnation instead of sympathy after those attacks, saying “the American cowboys are reaping the fruit of their crimes against humanity,” but that was the extent of his involvement. Regardless, this myth does contains one nugget of truth: The Iraq War was used by terror groups as a recruiting tool, and the presence of non-Muslim militaries in Muslim lands was, to them, an unforgivable outrage.

That means that the war in Iraq helped us defeat al-Qaeda. Fighting the “infidels” in Iraq and Afghanistan took strategic precedence over acts of terror in the U.S. and Europe. The “best” al-Qaeda terrorists went up against well-armed soldiers; incompetent regional organizations and ‘lone wolves’ tried—and usually failed—to take the fight to innocent civilians in the west. Bush and the coalition military leaders probably didn’t plan it that way . . . but it worked.

Myth #9: “Bush Lied, People Died”

Those of us who lived through the Iraq War period heard the empty antiwar catch-phrase over and over: “Bush lied, people died.” This was often accompanied by a demand that Congress impeach Bush and remove him from office.

Did Bush lie? If he did, would it have warranted impeachment and removal?

The supposed lie was that Iraq had WMDs. Well . . . they did. Go back and re-read the fourth myth. It is true that Iraq’s WMD programs were less advanced than Bush said they were, so on that point he was either lying—a moral offense if not a legal one—or he believed he was telling the truth. The evidence supports the latter hypothesis.

Bush’s claims were closely aligned with those of his predecessor. President Bill Clinton (D) said in 1998, “The international community had little doubt [after the Gulf War], and I have no doubt today, that left unchecked, Saddam Hussein will use these terrible weapons again. . . . This situation presents a clear and present danger to the stability of the Persian Gulf and the safety of people everywhere. . . . Without a strong inspection system, Iraq would be free to retain and begin to rebuild its chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons programs in months, not years.”

Hussein wanted the world to be confused about whether or not he had a large, growing stock of WMDs. His subterfuge was successful—perhaps more-so than he intended. American intelligence agencies, and most others, believed the program was far more advanced than it was. U.N. weapons inspectors thought so too. The UNSC passed resolutions to condemn those programs. Exactly how so many professional intelligence analysts fell for this deception is still a mystery, but Bush—like Clinton and so many others—likely believed what they were saying. They were acting in good faith.

Let’s pretend, for the sake of argument, that Bush did lie. Would that warrant impeachment? The U.S. Constitution says, “The President . . . shall be removed from Office on Impeachment for, and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other High Crimes and Misdemeanors” (Article II, Section 4). A good rule-of-thumb is that serious crimes while in office (like felonies) warrant impeachment. Minor crimes, or things that aren’t crimes at all, don’t. The most-recent impeachment at the the time was when the U.S. House impeached Clinton for perjury and obstruction of justice; he was acquitted in the U.S. Senate.

The simplistic argument some made for a Bush impeachment was this: Clinton was impeached for lying, so Bush should be too. This glossed over an important distinction. Clinton lied under oath in a court of law. That’s a crime. Lying to the public, in-and-of itself, isn’t. (If it was, we’d have to impeach pretty much every high-ranking political official, wouldn’t we?) When public officials lie to the public, it is morally reprehensible and often politically destructive. That doesn’t make it a crime. It’s not impeachable.

Myth #10: Iraq is Worse-Off Now

Human rights violations under Saddam Hussein’s regime are well-documented. In April 2002, a resolution adopted by the U.N. Commission for Human Rights said that Hussein’s government had continually committed “systematic, widespread[,] and extremely grave violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.”

Under Hussein, only members of the Arab Ba’ath Party had voting rights—less than eight percent of the population. Citizens could not demonstrate against the government. People would be arrested without being told what they were charged with, and their families wouldn’t even be told that they were in custody. Loved ones just disappeared; sometimes you never saw them again.

In the prisons, brutal torture was the norm—things that made the Abu Ghraib abuses look trivial by comparison. Rape was a political tool. Prisoners could be executed for minor offenses, or at random to reduce the prison population. People had their limbs amputated or were branded with hot irons for minor crimes like petty theft. Coalition forces found torture centers in police stations with electric shock devices and blood-soaked hanging hooks. They also found countless mass-graves, some containing thousands of bodies.

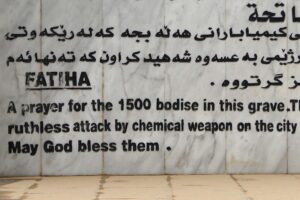

Hussein is one of the only leaders in history who used chemical weapons against his own citizens. In 1998, he killed more than 50,000 Iraqi Kurds—men, women, and children alike—with mustard gas and nerve agents. About 230,000 more Iraqis were killed in massacres after the Gulf War. Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Dexter Filkins, writing for the New York Times Magazine in 2007, said, “[Hussein] murdered as many as a million of his people, many with poison gas. He tortured, maimed[,] and imprisoned countless more. . . . More insidious, arguably, was the psychological damage he inflicted on his own land. Hussein created a nation of informants—friends on friends, circles within circles—making an entire population complicit in his rule.”

Of course, the people of Iraq also suffered during the invasion and occupation. Afterwards, they suffered under sectarian violence, al-Qaeda terror attacks, an Islamic State-led civil war, and other calamities. But family members aren’t disappearing into prisons to be raped and killed. Nobody is sent home with amputated limbs and permanent brands after years in custody. The Iraqi people can vote and influence their government. There are no new mass graves.

Is Iraq worse off today than it was under Hussein? No. That’s a dumb question.

The people of Iraq have a chance. They have it because we (some of us, anyway) sincerely believe in freedom and self-determination. More than 4,800 coalition soldiers and 3,600 military contractors died to buy that chance for them. More than 32,700 soldiers and 43,800 contractors were injured. We did not have to make this inconceivable sacrifice for people we don’t know in a country far away, but we did. And we did it on principle.

Now it is up to them. The citizens of Iraq can choose freedom and prosperity, if they want it. Like I said in 2009, they have “an opportunity to emerge from tyranny, and if they fail to seize [it] they have nobody to blame but themselves.” Like I said in 2014, paraphrasing a quote attributed Benjamin Franklin, “we gave the people of Iraq a republic . . . but it was their job to keep it.”

Editor’s Note, February 6, 2024: This article has been reviewed, reconsidered, rewritten, and republished. The list of myths is essentially unchanged, as are the conclusions, but each section has undergone too many changes to list. These mostly improve grammar, flow, and clarity. Some would qualify as a “substantial change of meaning” under the Tangent Style Guide if I had thought to list them out as I was making my edits.