The first of former President Donald Trump’s (R) many indictments were issued by a New York grand jury on March 30, 2023. Trump appeared at the Manhattan Criminal Courthouse on April 4 and entered a “not guilty” plea. The thirty-four-count indictment and an associated “Statement of Facts” were released to the public later that day.

The indictment alleges that Trump violated New York state law by falsifying business records. The case is related to “hush money” payments made through “Lawyer A” to “Woman 2” that were intended to prevent public disclosure of a sexual affair the woman allegedly had with Trump in 2006.

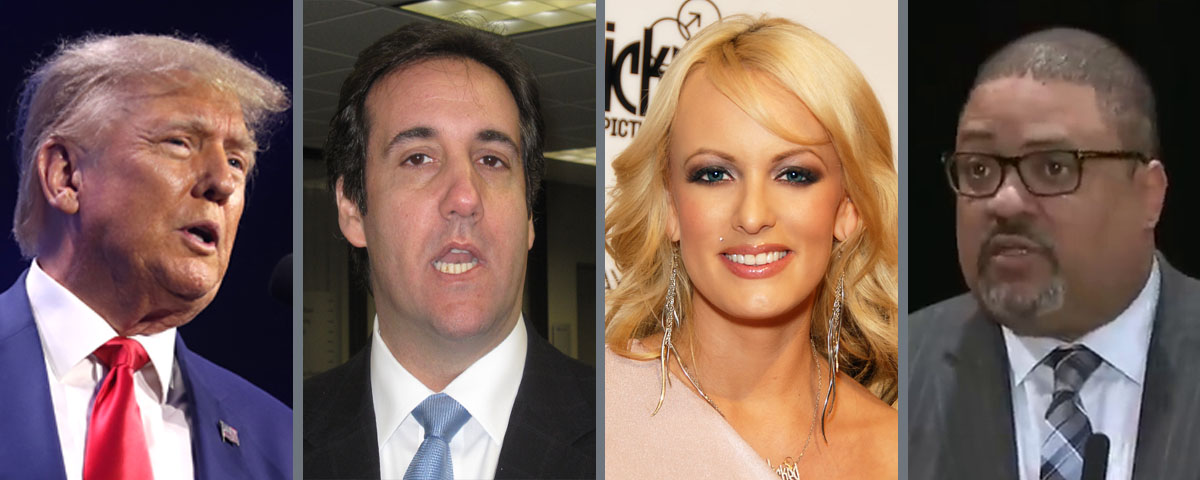

“Lawyer A” is believed to be Michael Cohen, who then worked for the Trump Organization as Special Council to Trump. I will refer to him by name in this article. “Woman 2” is believed to be adult film actress and director Stephanie Gregory Clifford, who is known professionally as Stormy Daniels. I will refer to her by her professional name in this review.

This article is based on the information that is publicly available at the time of its writing. It may need to be revised if new information becomes available. Any substantial changes will be described in the “Updates” section near the end of this post.

- Indictment (PDF)

- Statement of Facts (PDF)

Background

This indictment formally accuses Trump of falsifying business records, but the backdrop of the charges is described as a “scheme with others to influence the 2016 presidential election by identifying and purchasing negative information about him to suppress its publication and benefit the defendant’s electoral prospects.”

This so-called “catch-and-kill” scheme involved Trump and his campaign in coordination with American Media, Inc. (AMI), the publisher of magazines and tabloid newspapers including the National Enquirer, to buy exclusive rights to negative stories about Trump and then not publish them.

In connection with this scheme, AMI admitted guilt as part of a non-prosecution agreement with the federal government. Michael Cohen pleaded guilty and was convicted of eight federal charges including tax evasion, false statements, and illegal campaign contributions. Because Cohen entered a guilty plea, the charges were never contested before a judge and jury. I should also note that many of our campaign finance laws, including those under which Cohen was charged, are unconstitutional—they are either void under the “vagueness doctrine” in violation of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments’ due-process clauses, or directly violate the First Amendment’s free-speech protections.

The prosecution’s “Statement of Facts” alleges that Trump, Cohen, and AMI Chief Executive Officer David Pecker met at Trump Tower in August 2015—soon after Trump launched his presidential campaign—to arrange for AMI to act as the campaign’s “eyes and ears.” Pecker agreed that AMI would look out for negative stories and inform Trump and Cohen before any were published, and that AMI publications would run negative stories about other candidates.

Three examples of this “catch-and-kill” arrangement in-action are described by prosecutors.

In the first case, AMI paid $30,000 to a doorman at Trump Tower in New York City for exclusive rights to his claim that Trump fathered a child out of wedlock with a former employee. The accuser is identified only as “the doorman,” but is believed to be Dino Sajudin. AMI investigators later determined that Sajuin’s story was false. Other media outlets including The New Yorker were also unable to verify the claims.

In the second case, AMI paid a woman $150,000 in return for her silence about an alleged sexual affair she had with Trump in 2006 and 2007. She is identified only as “Woman 1,” but is believed to be model and actress Karen McDougal. Trump and Cohen agreed that they would reimburse AMI for the costs, and Cohen created a shell company called Resolution Consultants, LLC, for that purpose. AMI apparently called-off the reimbursement deal after consulting with attorneys.

The third case is the only one directly related to the charges in the indictment—the Stormy Daniels case. Daniels alleges that she had a sexual affair with Trump in 2006. Her attorney, who is identified as “Lawyer B,” contacted AMI and was referred to Cohen. The attorneys reached an agreement in which Trump would pay Daniels $130,000 in return for the exclusive rights to her claims. Trump, however, did not want to make the payments directly, so he instructed Cohen to arrange it.

Ultimately, Cohen created a new shell company—Essential Consultants, LLC—and transferred $131,000 from his home equity line of credit into its bank account. He then wired the $130,000 from that account to “Lawyer B.”

Trump and then-Trump Organization Chief Financial Officer Allen Weisselberg arranged to repay Cohen in twelve monthly installments of $35,000, for a total of $420,000. They arrived at that number by combining the $130,000 with an unrelated $50,000 expense for a total of $180,000, then doubled it to $360,000, then added a $60,000 year-end bonus. The reimbursement amount was doubled so that Cohen could claim the money as income but still receive at least $180,000 after taxes.

As agreed, Cohen submitted invoices in the amount of $35,000 for each month of 2017. Each of the eleven invoices (the first covered both January and February) stated that it was requesting “payment for services rendered” during the billable month “pursuant to the retainer agreement.” There was, in fact, no retainer agreement, and the invoices were not for services rendered in the claimed period. The Trump Organization paid the first two invoices—one for January and February, and one for March. The company categorized them as “legal expenses” and issued checks that said on the stubs that they were for “retainer[s].” The remaining nine invoices were paid by check from one of Trump’s personal accounts and then recorded by the company in its accounting system.

The prosecution’s “Statement of Facts” goes on to describe the federal investigation into Cohen, an alleged “pressure campaign” by Trump against Cohen after he began cooperating with investigators, AMI’s “admission of guilt” for paying Karen McDougal, and Cohen’s own guilty pleas—in which he claimed that he had committed crimes “in coordination with, and at the direction of” Trump.

Alleged Offenses

The charges in this case are thirty-four counts of “falsifying business records in the first degree” in violation of New York Penal Law §175.10. Each of the counts is substantially similar to the others, but the allegations fall into three general categories: Trump and the Trump Organization’s acceptance of Cohen’s false invoices, how the expenses were entered into the financial ledger, and how the checks and check stubs were issued and recorded.

Eleven of the counts allege that Trump made, or caused to be made, false entries in business records by accepting Cohen’s eleven invoices and recording them with the ledger code of “51505” (legal expenses). The invoices themselves also claimed they were for legal expenses during the preceding month(s) pursuant to a retainer agreement. As previously mentioned, Cohen submitted a combined invoice for the months of January and February, which is why there are only eleven counts. The counts covering the invoices are 1, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, and 32.

Twelve of the counts allege that Trump made, or caused to be made, false entries in the Trump Organization’s detailed general ledger by recording twelve voucher entries, each in the amount of $35,000, as legal expenses. These corresponded with Cohen’s invoices, but with January and February listed as separate line items, which is why there are twelve counts. The counts covering the voucher entries in the ledger are 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, and 33.

The remaining eleven counts allege that Trump made, or caused to be made, false entries in business records by recording copies of eleven checks and their associated check stubs, corresponding with each of Cohen’s invoices, as being for “retainer[s].” The combined January and February invoice was paid with one check, which is why there are eleven counts. Counts covering the checks and check stubs are 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28, 31, and 34.

Each of the counts include an allegation that the associated false entry was made “with intent to defraud and intent to commit another crime and aid and conceal the commission thereof.”

The Law

New York’s laws dealing with the falsification of business records are in section 175 of the state’s Penal Law:

- §175.00 defines a “business record” as “any writing or article, including computer data or a computer program, kept or maintained by an enterprise for the purpose of evidencing or reflecting its condition or activity.”

- §175.05 establishes the crime of “falsifying business records in the second degree.” It is a class-A misdemeanor to make a false entry in a business record, erase or destroy true entries a business record, omit a true business record in violation of duty, or cause others to do any of the above, with an intent to defraud.

- §175.10 establishes the crime of “falsifying business records in the first degree.” It is a class-E felony to commit the same crime as “falsifying business records in the second degree” if the intent to defraud includes “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.”

- §175.15 provides for an affirmative defense against prosecution for a “clerk, bookkeeper, or other employee who, without personal benefit, merely executed the orders” of his employer.

- New York’s Criminal Procedure Law recognizes “lesser included offenses.” For crimes with degrees, juries have the option to convict defendants of a lesser charge than the one for which they were indicted.

Each of the thirty-four charges filed against Trump in this case are under §175.10, “falsifying business records in the first degree.” Prosecutors are alleging that in each of these cases, Trump had an “intent to defraud” that included “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.”

Most of the important terms in the above laws are either self-explanatory or defined elsewhere in the law. There is an important exception: New York law makes an “intent to defraud” a necessary component of the crime, but does not define the term.

Analysis

Whether Trump should be convicted of falsifying business records (in either the first or second degree) hinges on the answers to the following questions about each count:

- Were business records falsified?

- Was Trump responsible for that falsification?

- Did Trump have an intent to defraud?

Whether Trump should be convicted of falsifying business records in the first degree also hinges on the answer to another question:

- Did Trump’s intent to defraud also include an intent to commit or cover-up another crime?

I will go through each of these questions in turn below. Because the thirty-four charges are substantially similar to one another, I will address them as a group instead of going through them one-by-one . . . but I will note cases where the analysis differs between the three classes of charges (eleven for the invoices, twelve for business ledger entries, and eleven for checks or check stubs).

I am writing this analysis on the assumption that the information in the indictment and “Statement of Facts” is essentially true; I have no reason to believe that it isn’t. If new information comes to light, I will update this article and note what changed in editor’s notes at the end.

Were business records falsified?

Business records under the law are “records ‘kept or maintained’ by the enterprise for the specific purpose of ‘evidencing or reflecting’ its condition or activity,” and can be stored either physically or electronically (McKinney’s 2023, §175.05 “Definitions”).

Each of Cohen’s invoices stated that they covered the preceding month’s expenses under a legal retainer, but there was no current retainer agreement at the time. The invoices were in fact for reimbursement of the money Cohen had sent to Daniels and others at Trump’s request, along with an annual bonus and additional funds to cover the expected taxes that Cohen would owe on the income.

Although Cohen was primarily responsible for creating and submitting the false invoices, Trump and Weisselberg knew what they were for and might have given Cohen instructions to submit them that way. When the invoices were accepted by Trump or his proxies and put into company records without correction, that constituted an act of falsification. Thus, for the eleven charges that deal with the invoices themselves, this condition was met.

Categorizing the payments to Cohen as legal expenses in the company ledger, however, is not even clearly wrong. Why wouldn’t it be a legal expense to reimburse your lawyer for money he spent on your behalf pursuant to an agreement he had facilitated? Why wouldn’t it be a legal expense to give your lawyer a bonus too? Perhaps there is an accounting rule, law, or regulation that says otherwise . . . but it is not cited in the charging documents. It would be difficult to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that a falsification even occurred for the twelve charges dealing with the ledger, let alone that it was done intentionally. Even if it could be clearly shown that the payments were mis-categorized, proving it wasn’t just an innocent error would be practically impossible.

As for the eleven charges dealing with the checks and check stubs, the fact that they were labeled as payments for a non-existent legal retainer, and related expenses in the stated month, was probably a falsification. However, the invoice and the payment of the invoice together make a single transaction, and so the checks and stubs should not be charged separately.

This raises an important point—it is inappropriate to issue multiple charges of the same crime for a single act. Each invoice, its associated ledger entries, and the check or check stub for its payment, should be treated as a single transaction and thus a single business record. In other words, Trump should be facing eleven charges, not thirty-four. The prosecutor seems so intent on pumping the number of charges that he even counted two ledger entries relating to line items on the same invoice as separate crimes—that is how we got to thirty-four charges for eleven transactions. I am not aware of any case law that addresses this specific situation, but New York courts have ruled that duplicate business records are not, in-and-of themselves, business records under this law (McKinney’s 2023, §175.05 “Definitions”).

The strategy of throwing charges at the wall to see what sticks is common. That does not make it right. Regardless of its ethics, it may be a bad strategy if the case ends up before a half-way intelligent jury.

Presenting eleven charges, each with three bits of supporting evidence, makes for a stronger total case than thirty-four charges where there is only one tiny bit of supporting evidence for each. If I were evaluating these thirty-four charges as a juror, twelve (the ledger entries) would be an almost immediate “not guilty,” and eleven more (the check stubs) would be strongly leaning toward “not guilty” since the alleged falsification was simply a repeat of what was in the invoices.

As I came back to look at the eleven strongest charges—the invoices—I would have developed a lean toward “not guilty” that I did not have initially. I would now know that I’m dealing with a prosecutor who has no ethical qualms about submitting a set of charges that is two-thirds junk. That makes the remaining charges suspect-by-default. I would likely put that aside, but then I would be considering only one piece of falsified information for each charge—the invoice. There’s still a case there, but it’s not a strong one.

Was Trump responsible for it?

Trump was aware of Cohen’s payment to Daniels, and of the reimbursement plan, and of the invoices from Cohen that falsely stated they were for current expenses under a retainer agreement. It is very likely that Trump was aware of the nine checks or stubs that came from Trump’s personal accounts falsely stating they were for a legal retainer. Trump, or somebody under Trump’s direction, submitted those falsified records to the Trump Organization.

It is also likely, though less so, that Trump was aware of the two checks or stubs that went to Cohen from the Trump Organization.

This condition has probably been met for the eleven invoice charges and the nine of the check or check stub charges. It would be met for the remaining two check or check stub charges if it can be proved that Trump was aware of them.

Trump would have a strong defense in saying, “Hey, I got these invoices from my lawyer that said they were for legal services, and I paid the invoices with checks that matched what the invoice said. How am I supposed to know that my trusted lawyer was sending me false invoices? I write thousands of checks every month. This was just another invoice in a pile.” I’m not saying I believe that. I don’t. But Trump does not need to convince a jury that he’s innocent, just that there is reasonable doubt.

I have not seen any clear evidence that Trump instructed Weisselberg or other Trump Organization officials to enter these transactions into the company ledger as legal expenses . . . so the twelve ledger charges are by-far the weakest. As previously discussed, they were on shaky ground to begin with, since it’s not even clear that the entries were false in the first place.

Was there an intent to defraud?

Even if Trump did falsify business records, conviction must hinge on whether he did so with an “intent to defraud.” This is a difficult difficult question because “there is no [New York] Penal Law definition of ‘intent to defraud’” (McKinney’s 2023, §175.05 “The Crimes”). Thanks, New York legislators!

First, let’s look at what general legal references say about what it means to “defraud” somebody:

- To defraud is “to cause injury or loss to (a person) by deceit.” – Black’s Law Dictionary (Garner 2019, “Defraud”)

- “Intent to defraud means an intention to deceive another person, and to induce such other person, in reliance upon such deception, to assume, create, transfer, alter, or terminate a right, obligation, or power with reference to property.” – Gale Encyclopedia of American Law (Batten 2010, “Defraud”)

- To defraud is “to deprive of something by fraud,” which is “a misrepresentation or concealment with reference to some fact material to a transaction . . . with the intent to deceive another . . . who is injured thereby.” – Merriam-Webster Law Dictionary (M-W Law 2023, “Defraud” and “Fraud”)

- Defrauding is “any act that deprives someone of something that is his or to which he might be entitled or that injures someone in relation to any proprietary right.” – A Dictionary of Law (Law 2022, “Defraud”)

In each of these definitions, being defrauded means that a victim has been injured in some way—they have been deprived of something to which they have a right. In both common and legal usage, “defraud” normally applies to money and property. It can occasionally apply to other rights. In one federal case, Carpenter v. United States (1987), the court defined “defraud” as “wronging one in his property rights . . . ” (McKinney’s 2023, §15.00 “Intent to Defraud”).

The phrase “intent to defraud” also appears in New York Penal Law §175.35, which establishes the crime of “offering a false instrument for filing in the first degree.” New York courts have broadly interpreted the phase under that statute—for example, in People v. Kase (1981), the court found that it “does not require an intent to deprive the victim of money, property rights, or a pecuniary [monetary] interest” (Greenberg 2022, §17:5). An intent to defraud is “often directed at gaining property or a pecuniary benefit,” but “need not be so limited” (McKinney’s 2023, §15.00 “Intent to Defraud”). The courts are split on whether this broad interpretation should be applied to the business records laws.

To cite two of the many examples, in People v. Schrag (1990) the court found that the business records statute was “not qualified by any language which limits their applicability to property or pecuniary [monetary] loss,” but another court found in People v. Hankin (1997) that an intent to defraud is “commonly understood to mean to cheat someone out of money, other property[,] or something of value” (Greenberg 2022, §17:5). The pattern Criminal Jury Instructions for this statute in New York use the narrower interpretation: “defraud” means “to cheat or deprive another person of property [or a thing of a value] [or a right]” (Greenberg 2022, §17:5; brackets in original).

As Greenberg concludes, the “conflict in the case law concerning the meaning of intent to defraud in the falsifying business records statute calls for resolution by the Court of Appeals or, perhaps more appropriately, the Legislature.”

As a matter of principle, laws should be interpreted under their plain meaning—how they would be commonly understood at the time they were adopted. The plain meaning of the term “defraud” is to use deceit to cause somebody a loss, especially, but not exclusively, in money or property. Depriving somebody of other rights could be defrauding them, but only in very direct and obvious cases. To establish an intent to defraud, we must clearly establish who was the intended victim and what they were going to be deprived of.

Prosecutors assert in each count that Trump falsified records “with intent to defraud,” but do not state who was to be deprived of what. The “Statement of Facts” does not contain the words “defraud” or “fraud” at all. There is only one instance of the word “fraudulently,” which appears in the first sentence: “[Trump] repeatedly and fraudulently falsified New York business records to conceal criminal conduct that hid damaging information from the voting public during the 2016 presidential election.”

Apparently, prosecutors are alleging that Trump’s intent to defraud was that he meant to deprive “the voting public” of “damaging information” about him.

Ideally, the voting public knows everything there is to know about a candidate . . . but there is no right to know privately held, non-governmental information about anybody. In this case, Daniels had a plausible claim about an affair with Trump; assuming she believed it to be true, she had the right to tell the whole world about it if she wanted to. But she also had the right to not tell anybody, or to sell the story, or to come to a private agreement with Trump for payment in return for silence.

Unless Daniels wanted to release that information to the public and was forced or otherwise coerced to keep quiet, the voting public was not deprived of anything they had a right to. Therefore, this condition has not been met.

Was there further criminal intent?

If all the above conditions were met, Trump could be convicted of falsifying business records in the second degree (a misdemeanor “lesser included offense” of the first-degree charges). An additional condition must be met to convict him of felony first degree falsification: The “intent to defraud” must also include “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.”

This question is (or should be) irrelevant, since the conditions for the lesser charge were not met. I will analyze the question anyway in the interest of completeness, and because new information could later change my previous analysis.

New York courts have interpreted the “intent to commit another crime” or “conceal the commission thereof” quite broadly. In People v. Dove (2007), the court found that the defendant could be guilty even if the crime they are hiding is somebody else’s (Greenberg 2022, §17:3). State courts have also found, in People v. McCumiskey (2004) and other cases, that the statute “does not require proof that the defendant committed or was convicted of the intended crime” at all (McKinney’s 2023, §175.05 “The Crimes”).

As with the “intent to defraud,” each count of the indictment asserts that Trump falsified records with “intent to commit another crime and aid and conceal the commission thereof.” There is no clear explanation of what that other crime might be.

The prosecution’s “Statement of Facts,” as quoted in the previous section, accuses Trump of falsifying the business records to “conceal criminal conduct.” The document further alleges that the scheme to “catch-and-kill” potentially damaging stories about Trump was unlawful, and that participants in the scheme “violated election laws” and “mischaracterized, for tax purposes, the true nature of the payments made in furtherance of the scheme.”

As described earlier in this article (“Background”), in AMI’s admission of guilt the company acknowledged that it intended to “influence that [2016] election.” Cohen, for his part, pleaded guilty and was convicted of tax evasion, campaign finance violations, and other crimes. The prosecution points to these facts as evidence of criminal activity that connects with these charges. But these accusations were never contested before a judge and jury; they are, at best, legally questionable.

AMI admitted that it bought stories to kill them and “thereby influence that [2016] election,” but influencing elections by publishing—or not publishing—a story about a candidate is not a crime. If it were, well, you had better charge me while you’re at it! It could be argued that AMI’s arrangement with the Trump campaign was an undocumented, in-kind campaign contribution . . . but that would require us to base the whole case on unconstitutional campaign finance laws. Many of the charges to which Cohen pleaded guilty also relate to campaign finances. Thus, the alleged other crimes are not crimes at all. The Bill of Rights outranks the U.S. Code.

The best argument for treating Cohen’s alleged crimes as other crimes for the purpose of charging Trump under this statute is that the structure of the reimbursement scheme might have been designed to help Cohen evade his taxes. To convict Trump for this, it would have to be demonstrated that he knew that was the reason the invoices and payments were set up the way they were, and that his intent in accepting them was to assist Cohen in the commission of that crime. This is plausible, but not proved.

In any case, New York case law relating to this clause is deeply flawed. Prosecutors are permitted to charge a defendant with having an “intent to commit another crime,” or to “conceal” one, but need not actually charge them with that other crime, or point to another indictment, or even articulate what crime the defendant allegedly intended to commit or conceal. In one case, People v. Holley (2021), a jury convicted the defendant of falsifying business records in the first degree but simultaneously acquitted the defendant of the alleged other crime! That insane outcome was upheld on appeal (Greenberg 2022, §17:3).

This is unconscionable. The case law is wrong.

Appearance of prosecutorial bias

Putting the strictly legal questions aside, we must also consider Trump’s (and others’) claims that New York County District Attorney Alvin Bragg (D) is prejudiced against the defendant. If so, this would violate the ethical principle that prosecutors “must be fair and unbiased” (Batten 2010, “District and Prosecuting Attorneys”).

During his campaign for District Attorney, Bragg routinely criticized Trump and accused him of wrongdoing. In a primary debate he said, “I have investigated Trump and his children and held them accountable. . . . I also sued the Trump administration more than 100 times.” In a radio interview he said, “I’ve seen him up front and seen the lawlessness that [Trump] could do. . . . I believe we have to hold him accountable.”

Bragg was careful not to speak about this specific case—adhering to the letter, if not the spirit, of the legal profession’s ethical standards. In the same interview cited above, he said, “I am being a little careful because I don’t want to prejudge and then . . . the first motion I get . . . is I got [sic] to recuse myself because I have prejudged the facts.”

To recuse is “to disqualify (as oneself or another judge or official) for a proceeding by a judicial act because of prejudice or conflict of interest” (M-W Law, “Recuse”). For example, judges or prosecutors will typically recuse themselves from cases involving friends or family members, or companies they do business with, or politicians they have publicly supported or opposed. This norm serves two purposes: First, it protects the accused from unfair prosecution and possible conviction by people who are prejudiced against them. Second, it demonstrates to outside observers that the judicial system is not swayed by either favoritism or vendettas—that is, that everybody gets a fair trial.

It is for the second reason that officials should recuse themselves even if there is only an appearance of bias. Maybe they really are being fair, or at least believe they are, but it looks bad. It leaves the public with the impression that the judicial system cannot be trusted.

Bragg’s repeated public criticism of Trump—though not directly related to this case—is sufficient reason for him to turn it over to another prosecutor. By continuing, he lends support to Trump’s claim that he is the victim of a “witch hunt.” If Trump is convicted, Bragg’s participation in the case provides a ready-made avenue for appeal.

It is troubling that Bragg has refused to recuse, but the charges should still be considered on their merits. If Trump is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of the crimes for which he is accused, he should be convicted. If not, he should be acquitted. Bragg’s participation in the case, though inappropriate, does not change that.

Conclusions

Given the above, we can come to some conclusions about this case—whether it is appropriately charged, and whether Trump should be convicted. This is complicated by two factors: First, New York case law (i.e., court precedent) includes improperly broad interpretations of some terms, and in one case the precedents are in conflict. Second, the charges rely on alleged violations of unconstitutional campaign finance laws that should be overturned or repealed, and must be considered void in the meantime.

As a result, there are two varying (but mostly overlapping) sets of conclusions—one set in the dysfunctional “real world,” and another in a hypothetical world where the U.S. Constitution is still in effect and laws mean what they say. The latter is the world I would prefer. I will note in the following conclusions where those worlds collide.

- Trump should be facing eleven charges, not thirty-four. It is inappropriate to treat false invoices, the record of those invoices in the ledger, and the check or check stubs paying those invoices, as three or more separate crimes.

- Not only does the inflation of the charge count make it look like prosecutors are throwing everything at the wall to see what sticks, it also weakens each individual charge.

- The presence of weak and interrelated charges in the set could prejudice a jury against all the charges. Ethical considerations aside, this is bad strategy. It would be better to present eleven strong charges than thirty-four weak ones.

- Business records were falsified. The invoices submitted by Cohen falsely claimed that they were for current charges under a legal retainer agreement. They were in fact reimbursements for past expenses—a payment to Daniels in return for her silence about an alleged affair with Trump—combined with an annual bonus and extra funds to cover taxes.

- This conclusion clearly applies to the eleven charges for the invoices themselves. It likely applies, but less definitively, to the eleven charges for the checks or check stubs stating they were for a legal retainer.

- This conclusion likely does not apply to the twelve charges relating to entries in the Trump Organization’s business ledger. The payments can be reasonably categorized as legal expenses, so it has not been proved that the entries are false at all.

- The nuance described above would be irrelevant if the charges had been combined, as they should have been, into a smaller number of stronger charges.

- Trump likely shares responsibility for the falsification. There is little doubt that Trump was aware of the arrangement with Cohen and was aware that these invoices were not for current legal expenses under a retainer agreement. Therefore he could be culpable for their entry into company records. Cohen, however, was the primary offender.

- This conclusion clearly applies to the eleven invoice charges and to the nine check or check stub charges for checks from Trump’s personal accounts. It likely applies, but less definitively, to the two check or check stub charges for checks from the Trump Organization.

- The twelve charges relating to the entry of these invoices as legal expenses in the company ledger, which are likely invalid for not even being falsifications (discussed above), have not been clearly attributed to Trump.

- Again, the nuance described above would be irrelevant if the charges had been combined.

- Trump did not have an “intent to defraud,” but it’s complicated because of bad case law. The New York Penal Code does not define the phrase. The state’s case law tends toward an improperly broad interpretation of the phrase as applied to another statute (§175.35), but the courts have split on whether that standard applies to the relevant statutes in this case (§175.05 and §175.10).

- Under a proper interpretation of the phrase—the plain, common meaning—an “intent to defraud” would mean an intent “to cause injury or loss to (a person) by deceit” (Garner 2019, “Defraud”). Under this definition, Trump’s alleged intent to deprive “the voting public” of “damaging information” about him does not meet the conditions of the statute.

- Under the narrower interpretation of the phrase in New York case law, and under the state’s pattern Criminal Jury Instructions, the above analysis holds true—Trump did not have an “intent to defraud” under the law.

- The broader interpretation of the phrase in New York case law is so vague as to be practically meaningless. If this absurd definition is used, a jury could find that Trump did have such an intent. But this interpretation is clearly improper and should not be used.

- The conditions of the crime are not met, so Trump should be acquitted. An “intent to defraud” is a necessary component of the New York state crime of “falsifying business records” in either degree. If we interpret the term properly, there is no evidence of such intent.

- As described above, an improperly broad interpretation of the term has been applied by New York courts under another statute, and the courts have split on whether that broad interpretation should apply here.

- If this case goes to trial and the broad interpretation is applied, it may be determined that the condition of an “intent to defraud” is met. This would be improper, but consistent with New York case law.

- Claims of further criminal intent are not proved, and there’s more bad case law. For “falsifying business records” to be charged as a felony, it must also include “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.” Such intent is asserted but has not been proved.

- New York case law on this subject is appalling. Prosecutors are free to allege virtually anything. They don’t have to indict the defendant for the other supposed crimes, or point to other indictments, or even articulate what other crime the defendant allegedly intended to commit or conceal.

- The other crimes described by prosecutors are mostly violations of campaign finance laws, which are unconstitutional and must be considered void. Tax evasion by Cohen is also mentioned, and it is plausible that the reimbursement plan was crafted to enable Cohen to commit a tax crime, but it has not been proved.

- The question of further criminal intent only becomes necessary if it is found that Trump had an “intent to defraud” as described above. It would be possible for jurors to find that Trump did have the intent to defraud, but did not have further criminal intent, and thus convict him of the “lesser included offense” of falsifying business records in the second degree—a misdemeanor.

- Bragg should recuse (disqualify) himself from the case. During his campaign to become District Attorney, Bragg regularly criticized Trump and accused him of wrongdoing. This presents an appearance of bias.

- Bragg was careful not to address this specific case during his campaign, thereby avoiding a direct violation of his profession’s ethical standards, but he should not have spoken about Trump at all given the circumstances.

- Whether Bragg is actually biased against Trump is not clear, but it is irrelevant. Recusal is a tool that is meant to protect defendants, yes, but also to demonstrate to the public that the judicial system is fair. The mere appearance of bias warrants recusal.

- By refusing to recuse, Brag undermines public perception of the case, enflames political criticism, and opens avenues for appeal in the event of a conviction.

The above conclusions can be summarized as follows:

- Counts 1, 5, 8, 11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, and 32, “Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree” – Not guilty (Trump).

- Business records (i.e., the invoices) were falsified, and Trump was aware of it.

- There was no legally actionable “intent to defraud,” so the conditions of the crime are not met.

- There is no evidence of further criminal intent, so charging in the first degree is improper.

- Counts 2, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 21, 24, 27, 30, and 33, “Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree” – Not guilty (Trump).

- Categorizing the ledger entries as legal expenses was not even clearly wrong.

- Thus, the very first condition of the crime is not met . . . and certainly not beyond a reasonable doubt. These charges are completely improper.

- Counts 4, 7, 10, 13, 16, 19, 22, 25, 28, 31, and 34, “Falsifying Business Records in the First Degree” – Not guilty (Trump).

- The checks and stubs were falsified, and Trump was aware of it.

- It is improper to treat the checks and stubs as separate records from the invoices; these counts should have been merged into the invoice counts.

- Regardless, there was no actionable “intent to defraud,” nor was there evidence of further criminal intent.

These conclusions are based on the facts as I understand them today. New evidence could change them. If that happens, I will reevaluate the affected parts of this article and add notes in the “updates” section below to describe changes.

Ed. Note, June 24, 2024: Trump was found guilty on all thirty-four counts by a New York jury on May 30, 2024. None of the information presented during the trial changes my analysis or conclusions. The jury’s conclusion was wrong, which is unsurprising (if depressing). The jury instructions were based in part on the bad case law described in this analysis. The conviction will likely be appealed by Trump, and will likely be overturned if the case receives a proper review by the higher courts.

Updates

This post will be updated when new information becomes available. I will include editorial notes in this section briefly explaining any substantial changes.

- June 24, 2024: This article has been updated with an editorial note briefly describing (and critiquing) the outcome of the trial, which concluded on May 30, 2024. Additionally, a simplified summary of the conclusions has been added for better consistency with the later articles in this series.

Notes

The feature graphic at the top of this article incorporates the photos listed below. They are licensed under Creative Commons licenses:

- Donald Trump by Gage Skidmore (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Michael Cohen by IowaPolitics.com (CC BY-SA 2.0)

- Stormy Daniels by Toglenn (CC BY-SA 3.0)

- Alvin Bragg by the Office of the Mayor of NYC (video still; 37:16) (CC BY 3.0)

Works Consulted

- Batten, Donna, editor. Gale Encyclopedia of American Law. Third Edition. 14 Volumes. Detroit, MI: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2010. Gale eBooks (via Fairfax County Public Library).

- Garner, Bryan A., editor. Black’s Law Dictionary. Eleventh Edition. Saint Paul, MN: Thomson Reuters, 2019. Westlaw (via Loudoun County Public Library).

- Greenberg, Richard A., editor. New York Criminal Law. Fourth Edition. New York Practice Series, Volume 6. Thomson Reuters, 2022. Westlaw (via Loudoun County Public Library).

- Law, Jonathan, editor. A Dictionary of Law. Tenth Edition. Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2022. Oxford Reference Online (via Library of Virginia).

- McKinney’s Penal Law. McKinney’s Consolidated Laws of New York Annotated, Book 39. Thomson Reuters, 2023. Westlaw (via Loudoun County Public Library).

- Merriam-Webster Law Dictionary (M-W Law). Online Edition. Merriam-Webster Inc., 2023. Merriam-Webster.com.

Series Links

- Part 1: Brief Overview

- Part 2: Business Records Case (New York) (this post)

- Part 3: Documents Case (Federal)

- Part 4: Election Case (Federal)

- Part 5: Election Case (Georgia)

- Part 6: Conclusions