The second of former President Donald Trump’s (R) indictments was issued by a federal grand jury on June 8, 2023, with a superseding indictment adding more charges on July 27. Trump appeared at the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida on June 13 and August 10 where he pleaded “not guilty.”

The indictment lists forty-two charges against three defendants—Trump himself and two of his aides, Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira. Thirty-three are directed at Trump alone (counts 1-32 and 38); four at Trump and Nauta (counts 34-37); three at Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira (counts 33, 40, and 41); one at Nauta alone (count 39); and one at De Oliveira alone (count 42).

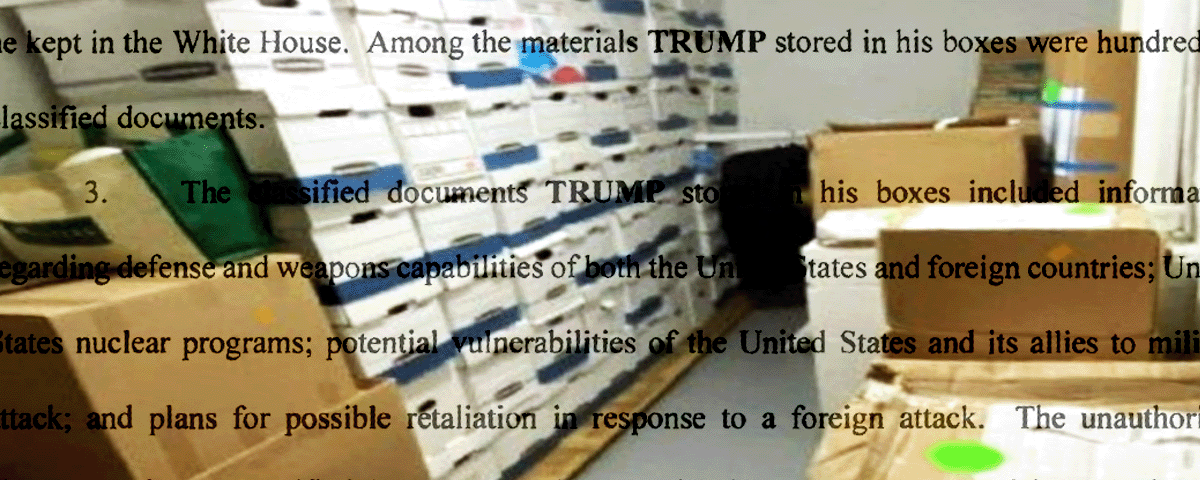

Prosecutors allege that Trump and his aides mishandled classified documents after the end of Trump’s presidency, concealed subpoenaed documents from a grand jury, and attempted to destroy evidence.

This article is based on the information that is publicly available at the time of its writing. It may need to be revised if new information becomes available. Any substantial changes will be described in the “Updates” section near the end of this post.

- Search Warrant and Affidavit (PDF) (with redactions)

Original Indictment(PDF) (superseded)- Superseding Indictment (PDF) (current)

Background

The indictment accuses former President Donald Trump (R) of transferring government-owned presidential records, including classified material, to his Mar-a-Lago resort, illegally retaining those records after the end of his presidency, withholding documents that had been subpoenaed by a federal grand jury, and attempting to destroy evidence.

Before analyzing each of the charges, we must review some relevant background information.

First, we must consider the requirements of the Presidential Records Act and how presidents are supposed to handle their records when they leave office. Prosecutors have not brought any charges under this act, but it is an important part of the context in which the alleged crimes occurred.

Next, we must understand what “classified” information is, including the levels of classification and the authority under which the classification system operates. This is directly germane to the first thirty-two counts, and secondarily to the rest. It will also help explain why the grand jury and FBI investigations were opened in the first place.

Finally, I will recount the sequence of events laid out in the indictment over the period from January 20, 2021—the last day of Trump’s presidency—to the FBI raid at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort on August 8, 2022.

Presidential Records Act

Under the Presidential Records Act (PRA) (44 USC §§ 2201–2209), most presidential documents are public property and must be turned over to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) at the end of a presidency. The law was adopted in 1978 and took effect on January 20, 1980—the beginning of the next presidential term.

Before the PRA, ownership of presidential records was not clearly defined. Presidents were free to decide on a case-by-case basis whether to treat them as public or private property. President Richard Nixon (R) treated his papers as private property; when he resigned in the aftermath of the Watergate scandal, he destroyed many of them. This prompted Congress to draft and eventually pass the PRA.

The law makes presidential and White House staff documents public property if they relate to the “constitutional, statutory, or other official or ceremonial duties of the President.” It also requires that the president keep those records, prohibits their destruction without in-writing approval by the Archivist of the United States, gives NARA custody after the end of a presidency, and establishes a schedule for records to be released to the public. The law does not apply to a president’s private documents like personal letters and journals.

The PRA does not specify penalties for violations, nor does it provide any mechanism for enforcement. There are, however, other laws that establish penalties for mishandling government documents that could be applied to PRA violations. For example, it is a federal crime under 18 USC § 2071 to unlawfully conceal, remove, mutilate, obliterate, or destroy “any record, proceeding, map, book, paper, document, or other thing” that is deposited in “any public office.” The person convicted of doing so “shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than three years, or both.” If the person was the official custodian of the record, then he “shall forfeit his office and be disqualified from holding any office under the United States.”

Section 2071 is designed to “prevent any conduct which deprives the government of use of its documents” (USCA 2023, § 2071 “Purpose”). Federal courts have held that White House offices like the National Security Council qualify as “public offices” under the statute (USCA 2023, § 2071 “Public Office”), and there is no reason to think that the president’s office would not qualify.

The law defines the custodian as the person who has “responsibility for care and guarding against harm of” a record (USCS 2023, § 2071 “Custody”), and can include “clerks or librarians” but also “others working in government agency who have access to sensitive documents” (USCA 2023, § 2071 “Custody of Records”). The president—who has primary responsibility for presidential documents under the PRA—would likely qualify as custodian under section 2071, but the provision disqualifying the violator from future office is likely inapplicable to a president on constitutional grounds.

As we will see later in this post, the PRA was violated by Trump hundreds of times. He should be prosecuted and convicted under section 2071, but prosecutors have so far declined to make any charges under that statute (or any other that may apply to PRA violations). Instead, Trump has been charged with violating laws relating to classification.

Classified Documents

Information is “classified” by the federal government when officials determine that the dissemination of that information could “damage the national security of the United States” (Sheppard 2012, “classified information”). When a document is classified, it is placed into one of three primary categories: “confidential,” “secret,” or “top secret.” Each has different restrictions on who may access the information and for what purposes it can be made available. Documents may receive secondary designations that include further restrictions.

This indictment describes the three categories of classified documents and the criteria under which a document should be marked with each (emphasis added):

- Top Secret: “The unauthorized disclosure of [this] information reasonably could be expected to cause exceptionally grave damage to the national security.”

- Secret: “The unauthorized disclosure of [this] information reasonably could be expected to cause serious damage to the national security.”

- Confidential: “The unauthorized disclosure of [this] information reasonably could be expected to cause damage to the national security.”

Classified information in the U.S. typically relates to the military, intelligence services, foreign policy, or nuclear energy—all of which fall under the executive branch.

Under the U.S. Constitution, “The executive Power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America” (Article II, Section 1). Note that executive authority is vested personally, not organizationally. Presidents must obey the law, of course, so long as those laws are duly enacted and constitutionally permissible . . . but within his branch of government, he is mostly free to act as he wishes. Those who work for him are bound by the orders he issues (assuming legality), but he cannot bind himself. If a president “violates” a previous presidential order, that is a de facto change or revocation of the original order.

Of course, presidents shouldn’t act in this manner. The fact that presidents have unique authorities does not make it okay to misuse them (morally speaking). When they act outside the norms they and their predecessors have established for the executive branch, it makes it difficult to understand what rules apply in what circumstances, sets a poor example for other officials, and undermines public trust. Something can be perfectly legal, but still be epically stupid.

Document classification falls under the original authority that presidents have on matters of national security. A president can classify and declassify at will, direct how classified information is used, and decide who to share it with. The classification system is governed by executive orders and executive branch policies, both of which fall under the president’s purview. For this reason, it is literally impossible for a sitting president to mishandle classified information (in a legal sense). When a president moves classified information outside its usual confines, that information has been de facto declassified.

When a public controversy relating to Trump and classified information came up in 2017, Senator James Risch (R-ID) said that the president “has the ability to declassify anything at any time without any process.” A PolitiFact analysis by Louis Jacobson found that legal experts were in broad agreement with that claim; he rated it “Mostly True.” It only fell short of a full “True” rating because “the particular situation involving Trump” at the time did not even involve declassification, so Jacobson thought Risch’s statement needed “clarification and additional information.”

(Curiously, the same writer at PolitiFact later analyzed essentially the same claim in relation to this case and rated it “False.” The newer article is . . . strange. Jacobson links to his original analysis and reasserts the key points of his previous conclusions: presidents can declassify at will, and they don’t have to follow any defined process to do it. Then he quotes a single dissenting lawyer, points to some tangentially related court cases, and reverses his conclusion . . . law and precedent be damned!)

Sequence of Events

Following is the sequence of events relevant to the accusations in the indictment. They are recounted based on the content of the indictment and other publicly available sources.

Departing Washington

The transfer of power between presidents occurs at noon on the January 20 following the election, regardless of when the inauguration ceremony is held or the oath of office is taken (U.S. Constitution, 20th Amendment, Section 1). At 59 seconds after 11:59 a.m. on January 20, 2021, Trump was still president. One second later, President Joe Biden (D) was.

Trump broke with longstanding tradition by skipping his successor’s inauguration. He was the first full-term president to do so since Andrew Johnson (D) snubbed Ulysses S. Grant (R) in 1869.

Trump left the White House at 8:13 a.m. and was flown by Marine One helicopter to Joint Base Andrews. Air Force One took off around 9:00 a.m. and arrived about two hours later at Palm Beach International Airport in West Palm Beach, Florida. Trump’s motorcade arrived at his home—Mar-a-Lago—around 11:30 a.m.; he would still be president for another half hour.

Mar-a-Lago was built in the 1920s as a mansion for Marjorie Merriweather Post. Upon her death in 1973, it was bequeathed to the U.S. government to become a “retreat for presidents and heads of state.” In 1981, the government returned the property to the Post Foundation due to high maintenance costs. The foundation sold it to Trump in 1985 (“Trump Takes Possession of Mar-a-Lago,” Miami Herald, December 29, 1985). He later converted the property into a high-priced private club with a $100,000 initiation fee; “early bird” applicants who signed up before its 1995 opening could join for half price (“Mar-a-Lago Club Membership List a Real Who’s Who,” Palm Beach Post, December 12, 1994).

According to the indictment, the Mar-a-Lago Club now includes “Trump’s residence, more than 25 guest rooms, two ballrooms, a spa, a gift store, exercise facilities, office space, and an outdoor pool and patio.” It has “hundreds of members” and “more than 150 . . . employees.” Over a twenty-month period described by prosecutors, it “hosted more than 150 social events, including weddings, movie premieres, and fundraisers that together drew tens of thousands of guests.”

As his term as president was coming to an end, Trump had his White House staff pack numerous boxes of documents and papers to be moved to Florida. The indictment states that Trump then “caused his boxes, containing hundreds of classified documents, to be transported from the White House to the Mar-a-Lago Club.” Prosecutors do not provide a detailed timeline of the movements of these boxes; they were packed “as he was preparing to leave the White House” and were stored at Mar-a-Lago “from January.” It is unclear if they were on Air Force One with Trump on January 20, or if they were moved separately.

In any case, about eighty of these boxes were first stored in Mar-a-Lago’s “White and Gold Ballroom,” then moved in-turn to the business center, a bathroom and shower at the “Lake Room,” and finally to a storage room on the ground floor of the club.

Many of the documents in these boxes were public records covered by the PRA and should have been turned over to NARA. According to the indictment, they also included “information regarding defense and weapons capabilities of both the United States and foreign countries; United States nuclear programs; potential vulnerabilities of the United States and its allies to military attack; and plans for possible retaliation in response to a foreign attack.”

Prosecutors allege that, “Trump was not authorized to possess or retain those classified documents.”

Investigations Begin

As discussed above, the PRA gives NARA the responsibility to maintain presidential records. Starting in March 2021, NARA officials began demanding that Trump return all presidential records still in his possession. The demands were ignored or dismissed until NARA finally threatened to refer the matter to the Department of Justice. In January 2022—a year after the end of his presidency—Trump and his aides gave fifteen boxes of records to NARA.

NARA officials reviewed the contents of those boxes and found 197 documents with classification markings. They reported their findings to the Justice Department, and on March 22. 2022, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) launched an official investigation into the “unlawful retention of classified documents at the Mar-a-Lago Club.” A federal grand jury took up their own investigation soon after.

Trump and his aides claimed they had no other PRA or restricted documents at Mar-a-Lago during this period. They were lying. At least sixty-four boxes remained in the ground-floor storage room.

Grand Jury Subpoenas

The federal grand jury issued a subpoena on May 11, 2022, instructing Trump to produce any documents with classification markings still in his possession.

A lawyer identified as “Trump Attorney 1,” who is believed to be M. Evan Corcoran, arranged to search for any responsive documents that might be stored in the boxes at Mar-a-Lago. In the days before that search was set to occur, Nauta, at Trump’s direction, moved the sixty-four boxes from the storage room to Trump’s private residence. On the day of the search, Nauta and De Oliveira moved thirty of those boxes back to the storage room.

Corcoran searched the boxes in the storage room on June 2, 2022, and found thirty-eight documents with classification markings. He was not told about the boxes now stored in Trump’s residence. Corcoran delivered the documents he had found to federal authorities the next day. Trump’s attorneys certified that a complete search had been made and all responsive documents had been provided.

The grand jury issued another subpoena on June 24, 2022, instructing Trump to provide “all surveillance records, videos, images, photographs[,] and/or CCTV from internal cameras” around the storage room. On June 27, De Oliveira—acting on instructions from Trump and Nauta—told “Trump Employee 4,” who is believed to be Yuscil Taveras, to delete security camera footage from the server. Taveras refused, despite De Oliveira’s attempts to pressure him.

Search Warrant

On August 8, 2022, the FBI executed a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago. They were authorized by the court to search for, and seize, any additional documents with classification markings. According to the indictment, agents found boxes of presidential documents in “a ballroom, a bathroom and shower, an office space, [Trump’s] bedroom, and a storage room.” Among the documents in those boxes, they found and seized 102 with classification markings.

In total, at least 337 documents with classification markings had been moved from the White House to Mar-a-Lago—197 in the set of documents given to NARA in January 2022, 38 provided in response to the grand jury subpoena in June 2022, and 102 seized by the FBI while executing the search warrant in August 2022. The total number of documents kept by Trump in violation of the PRA is unknown.

Special Council

On November 18, 2022, Attorney General Merrick Garland (D) appointed former federal prosecutor Jack Smith as special counsel to take control of two federal investigations of Trump—this one, and another relating to the Capitol riot on January 6, 2021. Smith’s office of special counsel has since obtained indictments from federal grand juries as part of both investigations (the one dealing with the Capitol riot will be addressed in a later post).

According to the indictment, of the 102 documents seized by the FBI, seventeen were marked “Top Secret,” fifty-four were marked “Secret,” and thirty-one were marked “Confidential.” These included material from the Central Intelligence Agency, the Department of Defense, the National Security Agency, the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency, the National Reconnaissance Office, the Department of Energy, and the Department of State’s Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

The specific charges contained in the indictment are described in detail below.

The Charges

The remainder of this post is a review of the charges contained in the indictment grouped into logical sets. For each, I will review the alleged offenses, describe the applicable laws, analyze the facts and evidence, and reach a conclusion about whether the defendants should be convicted.

Charges are made against former President Donald Trump (R) and two of his aides—Walt Nauta and Carlos De Oliveira. I am focusing on the counts where Trump has been charged, but I will also briefly cover the standalone counts directed at Nauta and De Oliveira.

I have arranged the charges in this manner:

- Retaining Documents

- “Willful Retention of National Defense Information” (counts 1-32, Trump)

- Hiding Documents

- “Withholding a Document or Record” (count 34, Trump and Nauta)

- “Corruptly Concealing a Document or Record” (count 35, Trump and Nauta)

- “Concealing a Document in a Federal Investigation” (count 36, Trump and Nauta)

- “Scheme to Conceal” (count 37, Trump and Nauta)

- “False Statements and Representations” (count 38, Trump)

- Destroying Evidence

- “Altering, Destroying, Mutilating, or Concealing an Object” (count 40; Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira)

- “Corruptly Altering, Destroying, Mutilating or Concealing a Document, Record, or Other Object” (count 41; Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira).

- Conspiracy

- “Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice” (count 33; Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira)

- Other Charges

- “False Statements and Representations” (count 39, Nauta)

- “False Statements and Representations” (count 42, De Oliveira)

Retaining Documents (Counts 1-32)

Thirty-two counts of the indictment (counts 1-32) charge Trump with “Willful Retention of National Defense Information” in violation of 18 USC § 793(e).

Alleged Offenses

Prosecutors accuse Trump of “having unauthorized possession of, access to, and control over documents relating to the national defense,” and allege that he “did willfully retain the documents and fail to deliver them to the officer and employee of the United States entitled to receive them.”

Thirty-two specific documents are described. Each document came into Trump’s possession before the end of his presidency, but prosecutors allege that when his term ended at 12:00 p.m. Eastern Time on January 20, 2021, his possession became “unauthorized.”

One charge relates to a document marked “Top Secret” that was turned over to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) on January 27, 2022:

- “Presentation concerning military activity in a foreign country” (count 32)

Ten charges relate to documents marked “Top Secret” that were turned over to the federal grand jury on June 3, 2022:

- “Document dated August 2019, concerning regional military activity of a foreign country” (count 22)

- “Document dated August 30, 2019, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to various foreign countries . . . ” (count 23)

- “Undated document concerning military activity of a foreign country” (count 24)

- “Document dated October 24, 2019, concerning military activity of foreign countries and the United States” (count 25)

- “Document dated November 7, 2019, concerning military activity of foreign countries and the United States” (count 26)

- “Document dated November 2019 concerning military activity of foreign countries” (count 27)

- “Document dated October 18, 2019, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to various foreign countries” (count 28)

- “Document dated October 18, 2019, concerning military capabilities of a foreign country” (count 29)

- “Document dated October 15, 2019, concerning military activity in a foreign country” (count 30)

- “Document dated February 2017 concerning military activity of a foreign country” (count 31)

Eleven charges relate to documents marked “Top Secret” that were seized by the FBI while executing its search warrant on August 8, 2022:

- “Document dated May 3, 2018, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to various foreign countries” (count 1)

- “Document dated May 9, 2018, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to various foreign countries” (count 2)

- “Undated document concerning military capabilities of a foreign country and the United States, with handwritten annotation in black marker” (count 3)

- “Document dated May 6. 2019, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to foreign countries, including military activities and planning of foreign countries” (count 4)

- “Document dated June 2020 concerning nuclear capabilities of a foreign country” (count 5)

- “Document dated June 4, 2020, concerning White House intelligence briefing related to various foreign countries” (count 6)

- “Undated document concerning military attacks by a foreign country” (count 9)

- “Document dated November 2017 concerning military capabilities of a foreign country” (count 10)

- “Undated document concerning military capabilities of a foreign country and the United States” (count 13)

- “Document dated January 2020 concerning military capabilities of a foreign country” (count 17)

- “Undated document concerning timeline and details of attack in a foreign country” (count 20)

Nine charges relate to documents marked “Secret” that were seized by the FBI while executing its search warrant on August 8, 2022:

- “Document dated October 21, 2018, concerning communications with a leader of a foreign country” (count 7)

- “Document dated October 4, 2019, concerning military capabilities of a foreign country” (count 8)

- “Pages of undated document concerning projected regional military capabilities of a foreign country and the United States” (count 12)

- “Document dated January 2020 concerning military options of a foreign country and potential effects on United States interests” (count 14)

- “Document dated February 2020 concerning policies in a foreign country” (count 15)

- “Document dated December 2019 concerning foreign country support of terrorist acts against United States interests” (count 16)

- “Document dated March 2020 concerning military operations against United States forces and others” (count 18)

- “Undated document concerning nuclear weaponry of the United States” (count 19)

- “Undated document concerning military capabilities of foreign countries” (count 21)

Finally, one charge relates to a document with no classification markings that was seized by the FBI while executing its search warrant on August 8, 2022:

- “Undated document concerning military contingency planning of the United States” (count 10)

The Law

The federal law under which Trump is charged is United States Code, Title 18, Section 793, “Gathering, transmitting[,] or losing defense information.”

This section was originally adopted as part of the Espionage Act of 1917, a controversial and largely unconstitutional law dating to World War I. Most of the Espionage Act was repealed after the war, but a few of its less controversial sections remained, including this one (Garner 2019, “Espionage Act”). The section was rearranged and clarified in 1950, and received minor amendments in 1986, 1994, and 1996 (USCA 2023, § 793 “Historical Notes”).

Each of the thirty-two counts are made under subsection (e):

Whoever having unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note relating to the national defense, or information relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit or cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted the same to any person not entitled to receive it, or willfully retains the same and fails to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it; . . . Shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both.

If Trump is convicted of the charges he is facing under this section, he could be imprisoned for up to 320 years or fined up to $8 million.

Analysis

Whether Trump should be convicted of “Willful Retention of National Defense Information” under this statute hinges on the answers to three questions:

- Were the documents “relating to the national defense?”

- Did Trump lack authorization to possess them?

- Did Trump willfully retain them anyway?

I will review each of these questions in turn. Because the thirty-two charges are substantially similar, I will address them together. Two counts—10 and 19—require special consideration and are discussed separately.

Were these defense documents?

To fall under the scope of section 793(e), a document must “[relate] to the national defense.” This phrase has been interpreted broadly. Courts have determined that “national defense is a generic concept of broad connotation,” and that the law does not “limit [the] reach of statute to purely military matters” (USCS 2023, § 793 “National Defense”).

Based on the brief descriptions of these documents given in the indictment, it is reasonable to assume that they qualify under section 793. They include documents relating to intelligence briefings, communications with foreign leaders, U.S. military planning and capabilities, foreign policy, and foreign military actions and capabilities.

If the given descriptions are accurate, this condition is likely met. There may be some room for case-by-case debate based on the contents of each document.

Did Trump lack authorization?

This is not an easy question to answer.

The president is the head of the executive branch, and in that capacity he has virtually unrestricted access to anything produced or possessed by executive agencies and departments. The military and intelligence services all fall under the executive branch; what they produce—even if it is classified—is also available to the president at his request. While Trump was president, he was legally authorized to possess all the documents cited in the indictment.

The question in this case is whether Trump was still authorized to possess them after his presidency ended at noon on January 20, 2021. Prosecutors argue that “Trump was not authorized to possess or retain classified documents” after that moment, and that the Mar-a-Lago and Bedminster clubs were not “authorized location[s] for the storage, possession, review, display, or discussion of classified documents.”

In support of this assertion, prosecutors cite Executive Order 13526, “Classified National Security Information,” which was issued by President Barack Obama (D) on December 29, 2009. Under that order, a person may generally access classified information only when “a favorable determination of eligibility for access has been made by an agency head or the agency head’s designee,” “the person has signed an approved nondisclosure agreement,” and “the person has a need-to-know the information.” There is a procedure for having some of these restrictions waived; Trump did not follow it.

Government employees may not store classified material in insecure facilities, give it to unauthorized persons, or retain it when they no longer have a legitimate need for it. This is true whether the employee is an Army soldier sending documents to Wikileaks, a Secretary of State storing them on an insecure private email server, or a Vice President stacking them in a garage behind his classic car.

Superficially, it looks like Trump violated the same rules. But this case differs from the others cited above in one important way: At the time he ordered the documents moved to Mar-a-Lago, Trump was the president. The sitting president is not an employee of the executive branch; he is the executive branch.

As described in the background section, the U.S. Constitution vests executive power in the President of the United States as a person, not as an organization. He is free to act however he wishes in the areas where he has original authority, including document classification. This means that when a sitting president directs that classified information be moved outside its normal confines, it is a de facto declassification.

Prosecutors seem to be aware of this and attempted to skirt around it in the indictment by obscuring the timeline of events. The indictment says, “At 12:00 p.m. on January 20, 2021, Trump ceased to be president. As he departed the White House, Trump caused scores of boxes, many of which contained classified documents, to be transported to The Mar-a-Lago Club. . . .” The wording falsely implies that Trump and the documents departed the White House on his orders after the end of his term. In fact, Trump left the White House nearly four hours before the transfer of power. The order to move the documents could not have been given any later than 8:13 a.m.

Thus, it was a sitting president who directed that the documents be moved to an insecure location and be put in the possession of persons who would not normally be authorized (i.e., himself after the end of his term, and his private staff). That order—good or bad, right or wrong, smart or dumb—was a de facto declassification order. From then on, they were subject to no security restrictions.

A presidential order stands until countermanded by another presidential order. Trump’s successor, President Joe Biden (D), could have re-classified the documents and ordered Trump to return them. Then Trump could have either complied with that hypothetical order or challenged it in court. But there is no evidence that Biden ever issued any such order.

There is another way Trump might have been “unauthorized” to possess these documents: He was supposed to have turned them over to NARA in compliance with the Presidential Records Act (PRA). Generally, the word “unauthorized” means “without authority or permission” (M-W Law 2023, “unauthorized”) or “done without authority” (Garner 2019, “unauthorized”). The plain text of the law, which is what good textualist jurists should be looking at, does not explicitly narrow the meaning. Thus, you could be in “unauthorized possession” of “information relating to the national defense” even if the reason the possession was unauthorized had nothing to do with national defense.

That interpretation would be out of step with precedent. In the context of section 793, the term “unauthorized possession” has always been understood in terms of national security classification (see USCA 2023, § 793 “Notes of Decisions” and USCS 2023, § 793 “Notes to Decisions”). I found no case law, and no previous prosecution, applying the term any other way. Precedent can be wrong . . . especially when so many jurists subscribe to interpretive philosophies based on political expedience and flim-flam. Sure, the legislative intent was almost certainly in line with the narrower interpretation of precedent, not the broader reading of the plain text. But we must interpret laws based on what they say, not what we think the legislators might have meant to say.

Regardless, prosecutors did not make this argument. They have based their charges only on the claim that Trump was “unauthorized” because he no longer had the authority to possess classified information after he was no longer president. That’s true, of course, but it doesn’t matter in this case because the documents weren’t classified anymore.

For counts 1-9, 11-18, and 20-32, this condition is not met. Trump should be acquitted.

For counts 10 and 19, refer to the “Special Considerations” section below.

If prosecutors had argued that Trump was “unauthorized” to possess the documents because of the PRA, that would have made for a somewhat stronger case . . . but it would have been inconsistent with precedent and thus likely to fail in the courts.

Rather than charging Trump under section 793, prosecutors could have brought hundreds of charges against Trump for violating the PRA by concealing or taking and carrying away public records under 18 USC § 2071(a)—one charge for every single presidential document in each of the sixty-four boxes. That they did not do this is inexplicable.

Did Trump willfully retain them?

A condition of each charge is that the accused “willfully retains the [document] and fails to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it.” Whether this condition is met is irrelevant because the “unauthorized possession” condition is not met, but I will evaluate it in the interest of completeness.

Trump directed that the documents be sent from the White House to Mar-a-Lago, and he kept them there. That is essentially undisputed. There may be a reasonable argument that the documents were not “willfully retained” before NARA demanded that they be returned . . . but after they did, there can be no doubt.

Trump dragged his feet on delivering the documents to NARA for nearly a year, and then he only delivered some of them.

This condition is met.

Special Considerations

Count 10

Count 10 relates to a document with no classification markings that was seized by the FBI while executing its search warrant on August 8, 2022. It is described in the indictment as an “Undated document concerning military contingency planning of the United States.”

It is possible that this document was supposed to be classified, but because it had no such markings there would have been no way for Trump (or anybody else) to know it.

Even if the de facto declassification of these documents had never occurred, and even if we were not discussing a former president, it would be practically impossible to prove that somebody in possession of a document with no classification markings could have known that it was restricted. It isn’t even clear why the FBI seized this document; the purpose of the search in August 2022 was to find “physical documents with classification markings.”

For count 10, the conditions of the charge are not met. Trump should be acquitted.

Count 19

Count 19 relates to a document marked “Secret” that was seized by the FBI while executing its search warrant on August 8, 2022. It is described as an “Undated document concerning nuclear weaponry of the United States.” Because this document deals with U.S. nuclear weapons, it could be subject to special restrictions.

Under 42 USC § 2014(y), “all data concerning (1) design, manufacture, or utilization of atomic weapons; (2) the production of special nuclear material; or (3) the use of special nuclear material in the production of energy” is “Restricted Data” unless it has been “declassified or removed from the Restricted Data category pursuant to [42 USC § 2162].”

The Department of Energy has responsibility for declassifying and removing documents from the restricted category if they “can be published without undue risk to the common defense and security.” If the restricted data relates “to the military utilization of atomic weapons,” the Department of Energy must make its determination jointly with the Department of Defense. If the energy and defense departments do not agree, “the determination shall be made by the President.” The two departments may also remove the restricted categorization from a document, but keep it classified, if they determine that it can be “adequately safeguarded as defense information.”

According to the indictment, the document in question was marked “SECRET//FORMERLY RESTRICTED DATA.” This indicates that the Energy and Defense departments removed it from the restricted category but did not declassify it.

Section 2162 does not clearly explain who has declassification authority for a document in this state. It gives the energy and defense departments the authority to add or remove a document from the restricted category, and to determine when a document should be “declassified and removed” (emphasis added), but it is conspicuously silent about who can declassify a document after it has been removed from the restricted category.

This strongly implies a transfer of that authority elsewhere—most likely back to the normal classification system that applies to other national security documents not in the restricted category. If so, this document would have been declassified at the same time and in the same manner as all the other documents.

It could be argued that the statute gives the Department of Energy a kind of “original jurisdiction” for any document that falls “within the definition of Restricted Data.” Perhaps a document could be “within the definition” even if it had been removed from the restricted category. That would be a clever [mis]application of the law, but it doesn’t work. The “definition of Restricted Data” in section 2014, subsection (y), specifically excludes “data declassified or removed from the Restricted Data category” (emphasis added).

Even if we accept an extremely stretched interpretation of the law and treat this document differently than the others, it does not matter. The Department of Energy and Department of Defense are both executive agencies under the president’s authority. His de facto declassification would still have applied, just through a different channel. Whether a president declassifies something under his original executive authority or through his headship of an executive department does not really matter. The document still gets declassified.

For count 19, the conditions of the charge are not met. Trump should be acquitted.

Conclusions

The conditions for “Willful Retention of National Defense Information” (counts 1-32) have not been met. Trump should be acquitted.

- Moving these documents to Mar-a-Lago was epically stupid.

- Trump was president when he ordered the documents moved. A presidential directive to move classified documents outside the classification system is a de facto declassification.

- After de facto declassification, the documents were no longer subject to restrictions. You cannot be in “unauthorized” possession of something that does not require authorization.

- Count 10 is particularly weak; the document did not even have classification markings.

- Count 19 is unique in that it deals with U.S. nuclear information that could be subject to additional restrictions. Even so, the president still had declassification authority.

- Trump violated the Presidential Records Act (PRA). He should have been charged (and convicted) under a more appropriate statue for that offense, such as 18 USC § 2071(a).

Hiding Documents (Counts 34-38)

Five counts of the indictment (counts 34-38) charge Trump and Nauta with offenses relating to alleged obstruction of the grand jury and FBI investigations: “Withholding a Document or Record” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(b)(2)(A), “Corruptly Concealing Document or Record” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(c)(1), “Concealing a Document in a Federal Investigation” in violation of 18 USC § 1519, executing a “Scheme to Conceal” in violation of 18 USC § 1001(a)(1), and making “False Statements and Representations” in violation of 18 USC § 1001(a)(2).

Alleged Offenses

Prosecutors accuse Trump and Nauta of making an organized effort to withhold evidence from two parallel federal investigations into Trump’s alleged retention of classified information.

As described earlier, a federal grand jury issued a subpoena on May 11, 2022, ordering Trump to turn over any documents in his possession that had classification markings. “Trump Attorney 1,” who is believed to be M. Evan Corcoran, and “Trump Attorney 2,” whose identity is unknown, informed Trump of the subpoena and scheduled a meeting to discuss it on May 23. At that meeting, Corcoran told Trump that they would need to search the property, collect responsive documents, and certify that they had complied with the subpoena.

Corcoran alleges that Trump suggested they either ignore the subpoena or lie and claim there were no such documents in his possession. The indictment includes several statements along those lines “memorialized” by Corcoran and attributed to Trump “in sum and substance.” In legal contexts, a “memorial” is a “written statement of facts” (Garner 2019, “memorial”). This means that Corcoran wrote down what he recalled Trump saying, but it is not clear whether the “memorial” was written immediately after the meeting or sometime later. Corcoran recalls Trump saying:

- “I don’t want anybody looking through my boxes, I really don’t. . . .”

- “Well what if we . . . just don’t respond at all or don’t play ball with them?”

- “Wouldn’t it be better if we just told them we don’t have anything here?”

- “Well look isn’t it better if there are no documents?”

Trump also allegedly referred to the mishandling of classified information by former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (D). Clinton famously used an insecure private email server to conduct official business, violating numerous classification and government records laws in the process. According to Corcoran, Trump praised Clinton’s attorney, who Trump believed had deleted Clinton’s emails and protected her from prosecution:

[Attorney], he was great, he did a great job. You know what? He said, he said that it – that it was him. That he was the one who deleted all of her emails, the 30,000 emails, because they basically dealt with her scheduling and her going to the gym and her having beauty appointments. And he was great. And he, so she didn’t get in any trouble because he said that he was the one who deleted them.

It is not clear who Trump was referring to here.

Over 31,000 emails were deleted when Paul Combetta, a technician with Platte River Networks, reduced the retention policy on Clinton’s private server to sixty days. Clinton chief of staff Cheryl Mills had requested the change before the House Select Committee on Benghazi subpoenaed Clinton’s emails, but Combetta did not do it at the time. When Mills later told Combetta about the subpoena, he had an “oh shit moment,” changed the policy (deleting the emails), and ran security software to ensure the deleted emails could never be recovered. Trump may also have been referring to David Kendall, an attorney who kept a USB “thumb drive” with copies of Clinton’s classified emails in a safe at his law firm.

Although Trump mixed-up some details, his point stands. Clinton violated the laws dealing with the handling of classified information and public records. Combetta destroyed evidence that was under subpoena. Kendall, Mills, and possibly others possessed classified information without authorization at various times. None of them faced prosecution. This does not exonerate Trump, but it does point to a troubling double-standard in how these laws are applied.

In any case, Trump, Corcoran, and “Attorney 2” agreed that Corcoran would return to Mar-a-Lago on June 2 to go through the boxes and find any documents responsive to the subpoena.

Between May 23 and June 2, at Trump’s direction, Nauta allegedly moved sixty-four boxes of documents from a Mar-a-Lago storage room to Trump’s residence. On June 2, shortly before Corcoran arrived, Nauta and De Oliveira moved thirty of them back to the storage room. When Corcoran arrived, Nauta escorted him to the storage room to make his search. Nobody told Corcoran there were more boxes in Trump’s residence.

Corcoran found thirty-eight documents with classification markings, placed them in a “Redweld folder” (an expanding, closable folder commonly used in law offices), and sealed it with “clear duct tape.” He then met with Trump, who asked, “Did you find anything? . . . Is it bad? Good?”

They discussed what would be done with the documents, eventually agreeing that Corcoran would take the documents to his hotel room and lock them in a safe overnight, then turn them over to federal officials the next day. During that discussion, Corcoran recalls:

He made a funny motion as though—well okay why don’t you take them with you to your hotel room and if there’s anything really bad in there, like, you know, pluck it out. And that was the motion that he made. He didn’t say that.

Corcoran prepared a certification that stated, in part, “A diligent search was conducted of the boxes that were moved from the White House to Florida,” and, “Any and all responsive documents accompany this certification.” He arranged for “Trump Attorney 3,” believed to be Christina Bobb, to sign the certification . . . even though she had not been involved in the search. The next day, the documents and signed certification were submitted to federal officials for delivery to the grand jury.

The Law

Trump and Nauta are charged with violating several federal laws covered in this section. Each applicable statute is described below, along with a brief description of the allegedly violative acts.

18 USC § 2 (Counts 34-38)

All five counts cite United States Code, Title 18, Section 2, “Principals,” which reads:

(a) Whoever commits an offense against the United States or aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces[,] or procures its commission, is punishable as a principal.

(b) Whoever willfully causes an act to be done which if directly performed by him or another would be an offense against the United States, is punishable as a principal.

This section establishes a principle that inducing or causing somebody else to commit a federal crime can be prosecuted as if they had committed it themselves.

Prosecutors referenced this section under numerous counts as a sort-of “catch-all” that allows them to hold the defendants responsible for things they did themselves and things they caused others to do on their behalf.

18 USC § 1512 (Counts 34-35)

Counts 34 and 35 fall under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1512, “Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant.”

In count 34, prosecutors claim that Trump and Nauta “did knowingly engage in misleading conduct toward another person, and knowingly corruptly persuade and attempt to persuade another person, . . . to withhold a record, document, and other object from an official proceeding” in violation of subsection (b)(2)(A).

Two alleged violations are cited: Trump’s suggestions to Corcoran that he ignore the subpoena, lie in response to it, or “pluck” documents out of the set was “corrupt persuasion,” and hiding the boxes from Corcoran was “misleading conduct.”

Subsection (b)(2)(A) reads:

Whoever knowingly uses intimidation, threatens, or corruptly persuades another person, or attempts to do so, or engages in misleading conduct toward another person, with intent to . . . cause or induce any person to . . . withhold testimony, or withhold a record, document, or other object, from an official proceeding . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

In count 35, prosecutors claim that Trump and Nauta “did corruptly conceal a record, document, and other object . . . with the intent to impair the object’s integrity and availability for use in an official proceeding” in violation of subsection (c)(1). Allegedly, by hiding the boxes from Corcoran the defendants were intending to hide them from the grand jury’s “official proceeding.”

Subsection (c)(1) reads:

Whoever corruptly . . . alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

If Trump or Nauta are convicted of the two charges they are facing under this section, they could be imprisoned for up to forty years or fined up to $500,000.

18 USC § 1519 (Count 36)

Count 36 falls under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1519, “Destruction, alteration, or falsification of records in Federal investigations and bankruptcy.”

In count 36, prosecutors claim that Trump and Nauta “did knowingly conceal, cover up, falsify, and make a false entry” in a record or object “with the intent to impede, obstruct, and influence” a federal investigation in violation of the section. Allegedly, hiding the boxes from Corcoran and making the false certification impeded the FBI’s ongoing investigation.

Section 1519 reads:

Whoever knowingly alters, destroys, mutilates, conceals, covers up, falsifies, or makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object with the intent to impede, obstruct, or influence the investigation or proper administration of any matter within the jurisdiction of any department or agency of the United States . . . or in relation to or contemplation of any such matter or case, shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

If Trump or Nauta are convicted of the single charge they are facing under this section, they could be imprisoned for up to twenty years or fined up to $250,000.

18 USC § 1001 (Counts 37-38)

Counts 37 and 38 fall under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1001, “Statements or entries generally.”

In count 37, prosecutors claim that Trump and Nauta did “falsify, conceal, and cover up by any trick, scheme, and device” a material fact from the grand jury and FBI investigations in violation of subsection (a)(1). The material fact being allegedly being covered up was Trump’s “continued possession of documents with classification markings.”

Subsection (a)(1) reads:

Except as otherwise provided in this section, whoever, in any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States, knowingly and willfully . . . falsifies, conceals, or covers up by any trick, scheme, or device a material fact . . . shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 5 years. . . .

In count 38, prosecutors claim that Trump did “make and cause to be made a materially false, fictitious, and fraudulent statement and representation” to the grand jury and the FBI in violation of subsection (a)(2). The alleged false statement was the certification that a “diligent search was conducted” in response to the subpoena and “all responsive documents” were delivered.

Subsection (a)(2) reads:

Except as otherwise provided in this section, whoever, in any matter within the jurisdiction of the executive, legislative, or judicial branch of the Government of the United States, knowingly and willfully . . . makes any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation . . . shall be fined under this title, imprisoned not more than 5 years. . . .

A notable exception to both parts of subsection (a) is given in subsection (b), which reads:

Subsection (a) does not apply to a party to a judicial proceeding, or that party’s counsel, for statements, representations, writings[,] or documents submitted by such party or counsel to a judge or magistrate in that proceeding.

If Trump is convicted of the two charges he is facing under section 1001, he could be imprisoned for up to ten years or fined up to $500,000. If Nauta is convicted of the single charge he is facing under section 1001, he could be imprisoned for up to five years or fined up to $250,000.

Analysis

The facts and statutes described above provide the background for the five charges in this section, but the specific conditions for each charge differ.

Count 34

Prosecutors have embedded two accusations within count 34. First, they allege that Trump attempted to “corruptly persuade” Corcoran to withhold documents that had been subpoenaed by the federal grand jury. Second, they allege that Nauta, at Trump’s direction, engaged in “misleading conduct” by hiding documents from Corcoran.

The claim of “corrupt persuasion” is based on Corcoran’s recollection (i.e., his “memorial”) of Trump’s comments and actions on two occasions.

First, on May 23, 2022, Trump said he didn’t want people going through the boxes, asked if they could just ignore the subpoena, and asked if it would “be better” for them to tell the grand jury that they had no documents. Trump then praised an attorney he believed had protected Hillary Clinton from prosecution.

Second, on June 2, 2022, after Corcoran searched the boxes in the Mar-a-Lago storage room, Trump “made a funny motion” that Corcoran interpreted as a request to “pluck” out “anything really bad.” But, Corcoran helpfully adds, Trump “didn’t say that.”

According to Corcoran’s own recollection of the meeting in May, Trump didn’t try to persuade him to do anything. Trump was asking questions and discussing options. It was reasonable for Trump to draw parallels with the Clinton case, and to ask his attorney whether he and his staff should respond to the subpoena the same way Clinton and her staff responded to theirs. There was a clear public precedent for such behavior going unpunished; disgraced former FBI Director James Comey said loudly and publicly that, “no reasonable prosecutor would bring such a case” against a public figure blithely mishandling classified information and then destroying the evidence.

The alleged “pluck” motion in June is (believe it or not) the stronger example of alleged “corrupt persuasion.” Trump might have been trying to tell Corcoran to withhold documents from the grand jury, which would indeed be a crime. Except, to quote Corcoran, “He didn’t say that.” There was just some “funny motion.” I suspect that Corcoran understood Trump’s meaning exactly as Trump meant it, but it could never be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Trump has a long history of making inexplicable “funny motions.”

The claim of “misleading conduct” against Nauta is much stronger. Whether hiding the boxes qualifies as “misleading conduct” under this section rests on the answers to three questions:

- Did Nauta intend to hide the boxes from Corcoran?

- Was hiding the boxes “misleading conduct?”

- Did hiding the documents result in them being withheld from an “official proceeding?”

The answers here are crystal clear. Nauta hid the boxes intentionally. Hiding them was “misleading conduct.” The intended result was that the hidden boxes, and the responsive documents inside them, would not be found by Corcoran and thus would not be turned over to the grand jury’s “official proceeding.”

The conditions are met. Nauta should be convicted.

Whether Trump should be convicted depends on the answer to one additional question:

- Did Trump willfully cause Nauta to commit the offense?

The answer to this question is clear too. Trump was calling the shots, and Nauta was acting on his behalf. The condition is met. Trump should also be convicted.

Count 35

It has been established above that Nauta, at Trump’s direction, hid boxes of documents from Corcoran for the purpose of withholding them from the grand jury; the applicable facts under count 35 are essentially the same as those under count 34.

Under the previous count, the defendants are accused of engaging in “misleading conduct” against Corcoran with the intent of causing him to withhold documents from the grand jury. Under this count, they are accused of directly impairing the documents’ availability to the grand jury.

Under section 2’s provision that a person who causes somebody to commit a crime can be charged as if they committed it themselves, it is appropriate to charge Trump and Nauta with withholding documents from the grand jury even though, strictly speaking, Corcoran withheld them (unwillingly as a result of the defendants’ actions).

The conditions are met. Both Trump and Nauta should be convicted.

Count 36

Prosecutors allege that withholding documents from the grand jury, and submitting the false certification, were attempts to “impede, obstruct, and influence the investigation . . . of any matter within the jurisdiction of a department and agency of the United States”—namely, the FBI investigation.

We must make a clear distinction between the two separate-but-overlapping investigations into Trump’s handling of classified documents. One was led by the FBI, which is a federal law enforcement agency under the executive branch. Another was led by a federal grand jury, which is an independent judicial entity. The FBI is a “department and agency” under this section; the grand jury is not.

Grand juries can gather evidence with subpoenas; in this case, they subpoenaed any presidential documents at Mar-a-Lago that had classification markings. Trump was required to provide all responsive documents, or else challenge the subpoena in court. The FBI does not have subpoena power and must rely on voluntary cooperation, or else convince a court that there is sufficient probable cause for a warrant.

To convict Trump and Nauta on this count, prosecutors would have to prove that the two alleged offenses—which were certainly intended to impede the grand jury investigation—were also intended to impede the FBI.

The first alleged offense was concealing boxes in Trump’s residence at Mar-a-Lago. By hiding them from Corcoran, the defendants ensured that at least some documents responsive to the grand jury subpoena would not be found and turned over. But any future FBI search of the property would occur under a search warrant, which would almost certainly give investigators access to Trump’s residence. Hiding the boxes there was effective against Corcoran, who was only given access to the storage room. It would not be effective against an FBI search; indeed, when that search did occur the FBI easily found the boxes.

The second alleged offense was the false certification submitted, according to the indictment, “to the FBI and grand jury.” This is another careless crossing of the wires between two separate investigations. FBI officials were present when Corcoran submitted Trump’s response to the grand jury subpoena, but they were there on behalf of the grand jury, not in their own investigative capacity.

The conditions are not met. Trump and Nauta should be acquitted.

Count 37

Prosecutors allege that Trump and Nauta’s efforts to hide documents and make a false certification “did knowingly and willfully falsify, conceal, and cover up by any trick, scheme, and device” a material fact from the grand jury and FBI investigations. The material fact in question is “the continued possession of subpoenaed documents.”

Once again, we must draw a clear line between the two separate investigations. Trump and Nauta had different obligations to the grand jury (which had issued a subpoena) than they did to the FBI (which had not yet obtained a search warrant).

Section 1001 has a “judicial function exception” that excludes any documents and testimony submitted to the courts by the subjects of their proceedings. Related case law includes U.S. v. Erhardt (1967), U.S. v. Abrahams (1979), and U.S. v. Mayer (1985) (USCS 2023, § 1001 “During judicial proceeding exception”). In 1996, when the statute was broadened to apply beyond the executive branch, a version of that “judicial function exception” was added to the text. It explicitly excludes from the scope of the law any items submitted by “a party to a judicial proceeding, or that party’s counsel . . . to a judge or magistrate in that proceeding.”

The exception has been broadly interpreted. For example, in U.S. v. McNeil (2004), the court determined that an inquiry into whether a defendant qualified for court-appointed counsel constituted a judicial proceeding. In U.S. v. Horvath (2007), the court found that a false statement to a probation officer fell under the scope of the exception because the officer was required to submit those statements to a judge (USCA 2023, § 1001 “Inquiries” and “Person to whom false statements or representations made”).

Most relevant to this case, the court ruled in U.S. v. Butler (2004) that there was “no basis to conclude that Congress intended [section 1001] to penalize false grand jury testimony at all” (USCS 2023, § 1001 “Cumulative or multiple punishments”).

Trump and Nauta certainly withheld material facts from the grand jury, which is a violation of federal law, but it is not a violation of this law. If these acts had been directed at the FBI, that would be different. The FBI does fall under the “executive, legislative, or judicial branch,” and its activities are normally not covered by the “judicial function exception.” But there is no evidence that Trump and Nauta were targeting the FBI when the hid the documents and made a false certification; they were targeting the grand jury.

FBI officials were present when Corcoran delivered Trump’s response to the grand jury subpoena, including the false certification. This is probably the basis of prosecutors’ claims that these acts were also intended to deceive the FBI, but that assertion is incompatible with well-established precedent.

In U.S. v. Deffenbaugh Industries (1992), the court found that a response to a grand jury subpoena, which had been submitted to the Department of Justice (DOJ), could not be prosecuted under this section because the DOJ does not have the authority to “require or request information sought by subpoena” or require “affidavit upon receipt” except on behalf of the grand jury (USCA 2023, § 1001 “Grand Jury”). In U.S. v. Wood (1993), the court found that the “judicial function exception” still applied even when the defendant made false statements directly to FBI agents when those agents were acting on behalf of a grand jury (USCS 2021, § 1001 “Federal Bureau of Investigation”).

The conditions are not met. Trump and Nauta should be acquitted.

Count 38

As discussed above (count 37), section 1001 cannot be used to prosecute the subject of a judicial proceeding for submitting false information as part of that proceeding. The “judicial function exception” has been part of the case law since 1967 and was formally codified into the law in 1996 (USCS 2023, § 1001 “During judicial proceeding exception”).

The FBI was involved in the hand-over of the grand jury response, but the FBI was acting as a go-between on behalf of the grand jury and the “judicial function exception” still applies.

The conditions are not met. Trump should be acquitted.

Conclusions

The conditions for the “Withholding a Record” charge (count 34), which is more accurately described as a “Corrupt Persuasion and Misleading Conduct” charge, have been met. Trump and Nauta should be convicted.

- The “corrupt persuasion” part of the charge, alleging that Trump tried to persuade Corcoran to withhold subpoenaed records or lie to the grand jury, has not been proved.

- The “misleading conduct” part of the charge, alleging that Nauta hid thirty boxes of documents from Corcoran, thus causing them to be withheld from the grand jury, has been proved.

- Trump was calling the shots and shares responsibility for the misleading conduct.

The conditions for the “Corruptly Concealing a Record” charge (count 35) have been met. Trump and Nauta should be convicted.

- As described above (count 34), Trump and Nauta hid thirty boxes of documents with the intent of concealing them from the grand jury.

The conditions for “Concealing a Document in a Federal Investigation” (count 36) have not been met. Trump and Nauta should be acquitted.

- The grand jury and FBI investigations were separate and distinct. An effort to impede one cannot be interpreted as an effort to impede the other without evidence.

- The effort to hide documents and make a false certification, thus impeding the grand jury investigation, could not have been expected to impede the FBI investigation.

The conditions for “Scheme to Conceal” (count 37) have not been met. Trump and Nauta should be acquitted.

- The statute includes a “judicial function exception” that does not allow prosecution for false testimony to a grand jury by the subjects of their investigations.

The conditions for “False Statements and Representations” (count 38) have not been met. Trump should be acquitted.

- This count falls under the same code section as count 37. For the same reasons described there, Trump’s actions fall under the “judicial function exception.”

Destroying Evidence (Counts 40-41)

Two counts of the indictment (counts 40-41) charge Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira with offenses relating to alleged attempts to destroy evidence: “Altering, Destroying, Mutilating, or Concealing an Object” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(b)(2)(B) and “Corruptly Altering, Destroying, Mutilating or Concealing a Document, Record, or Other Object” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(c)(1).

Alleged Offenses

Prosecutors accuse Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira of instructing “Trump Employee 4,” who is believed to be Yuscil Taveras, to delete security camera footage that had been subpoenaed by the grand jury.

As previously established, Nauta moved boxes of documents from a storage room into Trump’s residence for the purpose of hiding them from Corcoran and the grand jury. FBI agents were present at Mar-a-Lago on June 3, 2022, when the documents that Corcoran had found were turned over for delivery to the grand jury. Those FBI agents observed that there were security cameras on the property, including near the storage room where the documents had been stored.

The grand jury became aware of the security cameras—possibly from the FBI agents—and drafted a new subpoena for all the available footage from the cameras near the storage room. The Trump legal team received a copy of the draft subpoena on June 22. The final version of the subpoena was issued on June 24, requesting “all surveillance records, videos, images, photographs[,] and/or CCTV from internal cameras” for several locations at Mar-a-Lago, including the “ground floor (basement)” where the storage room was located.

At the time, Trump and Nauta were at Trump’s Bedminster Club in New Jersey with plans to travel to Illinois. When Trump learned of the subpoena, he sent Nauta back to Florida instead. Nauta and De Oliveira (who was already in Florida) contacted “Trump Employee 4,” who is believed to be Yuscil Taveras, and let him know that Nauta was coming. On June 25, Nauta and De Oliveira met at Mar-a-Lago to familiarize themselves with the security camera system.

On June 27, De Oliveira and Taveras went to the “audio closet” and De Oliveira inquired about how long video footage was stored on the server. De Oliveira went on, telling Taveras that “the boss” wanted the server deleted. According to the indictment, Taveras said that “he did not believe that he would have the rights to do that” and told De Oliveira to “reach out to another employee who was a supervisor of security for Trump’s business organization.” De Oliveira allegedly insisted, again saying that “the boss” wanted the files deleted. Taveras refused.

The Law

Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira are charged with violating two federal laws under this section. Each applicable statute is described below, along with a brief description of the allegedly violative acts.

18 USC § 2

Both counts cite United States Code, Title 18, Section 2, “Principals,” which reads:

(a) Whoever commits an offense against the United States or aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces[,] or procures its commission, is punishable as a principal.

(b) Whoever willfully causes an act to be done which if directly performed by him or another would be an offense against the United States, is punishable as a principal.

This section establishes a principle that inducing or causing somebody else to commit a federal crime can be prosecuted as if they had committed it themselves.

Prosecutors referenced this section under numerous counts as a sort-of “catch-all” that allows them to hold the defendants responsible for things they did themselves and things they caused others to do on their behalf.

18 USC § 1512

Counts 40 and 41 fall under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1512, “Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant.”

In count 40, prosecutors claim that Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira “did knowingly corruptly persuade and attempt to persuade another person” to “alter, destroy, mutilate, and conceal an object” with the intent of impairing its “availability for use in an official proceeding” in violation of subsection (b)(2)(B). De Oliveira allegedly told Taveras to delete subpoenaed security camera footage, and when he demurred De Oliveira tried to pressure him into doing it anyway.

Subsection (b)(2)(B) reads:

Whoever knowingly uses intimidation, threatens, or corruptly persuades another person, or attempts to do so, or engages in misleading conduct toward another person, with intent to . . . cause or induce any person to . . . alter, destroy, mutilate, or conceal an object with intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

In count 41, prosecutors claim that Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira “did corruptly alter, destroy, mutilate, and conceal a record, document and other object and attempted to do so” with the intent of impairing its “availability for use in an official proceeding” in violation of subsection (c)(1). De Oliveira allegedly attempted to delete the security camera footage.

Subsection (c)(1) reads:

Whoever corruptly . . . alters, destroys, mutilates, or conceals a record, document, or other object, or attempts to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

If Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira are convicted of the two charges they are facing under this section, they could be imprisoned for up to forty years or fined up to $500,000.

Analysis

The facts and statutes described above provide the background for the two charges in this section, but the specific conditions for each charge differ.

Count 40

Prosecutors allege that De Oliveira’s request to Taveras to delete subpoenaed video footage constituted an illegal attempt to tamper with evidence. Because the order to delete the footage originated with Trump, and was transmitted by Nauta, they are also charged under the section 2 principle that those who induce or cause a crime to occur can be charged as if they had done it themselves.

Section 1512 makes it a crime to pressure somebody to “alter, destroy, mutilate, or conceal an object” for the purpose of impairing “the object’s integrity or availability for use in an official proceeding.” It uses the same “corrupt persuasion” and “misleading conduct” phraseology discussed in the analysis of count 34.

If “the boss,” namely Trump, had in fact requested the videos’ deletion, then De Oliveira was not “misleading” Taveras by instructing him to do it. He was telling the truth. But Trump knew the footage had been subpoenaed, as did Nauta, so it clearly qualifies as “corrupt persuasion.”

The conditions are met for Trump and Nauta; they should be convicted.

In De Oliveira’s case, it is not clear if he knew the videos were under subpoena. He probably did—it’s hard to believe that Nauta hadn’t told him why they needed to delete them—but there is no proof described in the indictment.

The conditions are probably met for De Oliveira, but whether he should be convicted depends on if prosecutors can prove he knew the videos were under subpoena when he instructed Taveras to delete them.

Count 41

Prosecutors allege that De Oliveira, by telling Taveras to delete the video footage, did “corruptly alter, destroy, mutilate, and conceal a record, document and other object [or attempt] to do so, with the intent to impair the object’s integrity and availability for use in an official proceeding.”

The indictment presents no evidence that Trump, Nauta, or De Oliveira ever attempted to delete any footage themselves. Trump told Nauta, Nauta told De Oliveira, and De Oliveira told Taveras. When Taveras said he wouldn’t do it, De Oliveira tried to pressure him (see count 40). The only further action described by prosecutors is that, later that day, De Oliveira “walked back to the IT office that he had visited that morning.” They don’t say what, if anything, he did there.

To be convicted under this count, prosecutors would have to prove that Trump, Nauta, or De Oliveira attempted to destroy, mutilate, or conceal the security camera footage. Pressuring Taveras to do it was a crime as described under count 40, but a conviction under count 41 would require something more substantive.

The conditions are not met. Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira should be acquitted.

Conclusions

The conditions for “Altering, Destroying, Mutilating, or Concealing an Object” (count 40) have been met. Trump and Nauta should be convicted. De Oliveira should probably be convicted but it has not yet been proved beyond a reasonable doubt.

- Trump instructed Nauta to delete the subpoenaed security camera footage. Nauta traveled to Florida and communicated that request to De Oliveira, who then instructed Taveras to do it. Taveras did not.

- Trump and Nauta knew the security footage had been subpoenaed, so telling De Oliveira (who then told Taveras) to delete it was a crime.

- To convict De Oliveira, prosecutors would have to prove that he knew the video footage was under subpoena. He probably knew, but it has not been proved.

The conditions for “Corruptly Altering, Destroying, Mutilating or Concealing a Document, Record, or Other Object” (count 41) have not been met. Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira should be acquitted.

- De Oliveira attempted to pressure Taveras into deleting security camera footage, but Taveras refused. De Oliveira made no attempt to delete the videos himself.

- Prosecutors have presented no evidence that Trump, Nauta, or De Oliveira made any direct attempt to delete the security camera footage.

Conspiracy (Count 33)

One count of the indictment (count 33) charges Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira with “Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(k).

Alleged Offense

Prosecutors accuse Trump, Nauta, and De Oliveira (along with “others” who have not been identified) of engaging in a conspiracy to commit other crimes under section 1512. The indictment says they “did knowingly combine, conspire, confederate, and agree” to commit several alleged offenses, each corresponding with other counts in the indictment.

The purpose of the alleged conspiracy was for Trump to “keep classified documents he had taken with him from the White House and to hide and conceal them from a federal grand jury.”

The other offenses allegedly done in furtherance of the conspiracy are the violations of subsection (b)(2)(A) described in count 34, violations of subsection (b)(2)(B) described in count 40, and violations of subsection (c)(1) described in counts 35 and 41.

The Law

This charge is made under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1512, “Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant,” specifically subsection (k):

Whoever conspires to commit any offense under this section shall be subject to the same penalties as those prescribed for the offense the commission of which was the object of the conspiracy.

The offenses that the defendants allegedly conspired to commit fall under three other subsections.

Subsection (b)(2)(A) reads:

Whoever knowingly uses intimidation, threatens, or corruptly persuades another person, or attempts to do so, or engages in misleading conduct toward another person, with intent to . . . withhold testimony, or withhold a record, document, or other object, from an official proceeding . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

Subsection (b)(2)(B) reads: