The third of former President Donald Trump’s (R) indictments was issued by a federal grand jury on August 1, 2023. The four-count indictment was released to the public the same day. Trump appeared at the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia on August 3 where he pleaded “not guilty.”

Prosecutors allege that Trump engaged in three separate criminal conspiracies to subvert the results of the 2020 U.S. presidential election: One allegedly intended to defraud the United States and impede the lawful functions of the federal government (count 1), another to impede Congress’s counting of presidential electors on January 6, 2023 (count 2), and a third to impede citizens’ rights to vote and have their votes counted (count 4).

In connection with the second alleged conspiracy, prosecutors also accuse Trump of putting the plan into action by attempting to impede Congress’s counting of presidential electors on January 6, 2023 (count 3).

This article is based on the information that is publicly available at the time of its writing. It may need to be revised if new information becomes available. Any substantial changes will be described in the “Updates” section near the end of this post.

- Indictment (PDF)

Background

The charges in this indictment relate to crimes President Donald Trump (R) allegedly committed in the aftermath of the 2020 U.S. presidential election. To make sense of these events, we must start more than four years earlier.

We will briefly review the 2016 presidential election and some key events during Trump’s four-year term before turning to the 2020 election and the riot at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021. We will also look at some legal (and moral) matters relating to “conspiracy” as a standalone criminal offense.

Election 2016

On November 8, 2016, American voters went to the polls to decide who would become the forty-fifth President of the United States. The Democratic Party nominee was former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton (D). The Republican Party nominee was real-estate mogul and reality-TV star Donald Trump (R). Third-party and independent candidates included Gary Johnson (L), Evan McMullin (I), and Jill Stein (G).

Results

Pollsters and pundits were almost unanimous in predicting a comfortable win for Clinton. The expert prognosticators at FiveThirtyEight, then led by Nate Silver, estimated that Trump had a mere 28% chance of winning and that the most likely electoral outcome was 302-236 for Clinton. Silver’s industry peers thought FiveThirtyEight was seriously overestimating Trump’s chances. Sam Wang of the Princeton Election Consortium gave Trump a 7% chance and thought 323-215 for Clinton was the most likely result. The Los Angeles Times absurdly predicted a 352-186 landslide for Clinton. Larry Sabato’s Crystal Ball predicted 322-216 for Clinton, and helpfully added that, “Not even on Clinton’s worst campaign days did we ever have her below 270 electoral votes.”

I made no public prediction that year, but I also expected (and feared) a Clinton win. As I said when I reluctantly endorsed Trump, “The rapid erosion of human rights and civil liberties in the United States over the last decade has been frightening. Our republic, and the rights we hold dear, are now held in the balance by a tied [U.S. Supreme Court]. A Clinton presidency, and the statist [court] majority that will result, will likely mean the end of them. This is not hyperbole.”

We were standing on a precipice. I thought we were going to jump.

I made the same mistake that most pundits did. I failed to see that an alliance of malcontents had quietly formed behind Trump. They were a diverse crowd of people who were pissed-off, tired of “politics as usual,” desperate for a change, terrified of Clinton, or some combination of these and other factors. Trump made gains with “blue collar” voters who felt betrayed by globalization, lower-middle-class voters who had tired of a decade-long Bush/Obama malaise, Cuban American voters angry about Obama’s kowtowing to the socialists, pro-Israel voters frightened by warming relations with Iranian Islamists, immigration rationalists who saw the costs (and crimes) foisted on their communities by unchecked illegal immigration, and numerous other small blocs of Americans who felt abandoned by the powers-that-be.

Trump engaged these disaffected groups and pulled in voters who might otherwise have leaned toward Clinton. He also placated the skeptical Republican base (and independent conservatives like me) by offering a “short list” of possible Supreme Court nominees with solid textualist credentials and choosing then-Indiana Governor Mike Pence (R)—a trusted conservative figure at the time—as his running mate.

Meanwhile, Clinton was overconfident. She didn’t campaign enough in “blue collar” states like Michigan and Ohio. She made little effort to win-over the voters who supported Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) in the primary; she just assumed they would enthusiastically support her. Many did, of course, but not all. A sizable minority of Sanders supporters—especially those who cared about trade protectionism above all else—ended up in Trump’s corner.

When the voting was over, Trump had won 306 electors to Clinton’s 232. Ten “faithless electors” cast votes for other candidates when the electoral count was taken in the House of Representatives, but three of their votes were invalidated under state laws against the practice. The final tally was 304 electors for Trump, 227 for Clinton, 3 for former Secretary of State Colin Powell (R), 1 for former Ohio Governor John Kasich (R), 1 for former Representative Ron Paul (R-TX 14th), 1 for Sanders, and 1 for environmental activist Faith Spotted Eagle (D).

Clinton won the national popular vote by about two percentage points, or 2.87 million votes. The 2016 election was one of only five times when the winner of the presidential electoral vote did not also win the popular vote.

Denial

Many political observers—Clinton included—simply refused to accept the results. The idea that Trump won fair-and-square was simply incomprehensible to them. They soon concocted a conspiracy theory to rationalize it all away: Trump colluded with the Russian government to steal the election from Clinton. Even now, it is not clear if this was a lie they were telling the world or a lie they were telling themselves . . . but it was certainly a lie.

The “Russian collusion” conspiracy theory, like most persistent conspiracy theories, does contain a kernel of truth. Russia’s intelligence apparatus, at the behest of Russian President Vladimir Putin (United Russia), did try to interfere with the election . . . but they didn’t really care who won and didn’t coordinate with anybody’s campaign. Russia’s goal was to introduce chaos and instability. They wanted to weaken America from within.

During the primaries, the Russians mostly pushed the candidates they thought were most likely to sow anger and discord: Trump and Sanders. After Sanders dropped out the Russians shifted more toward Trump, but never completely. When undermining Trump was the more chaotic choice, they were happy to do it. The infamous “dossier” that Christopher Steele compiled about Trump for the Clinton campaign was full of Russian disinformation designed to hurt Trump. They were playing all sides, all the time. In one instance, Russian online trolls attempted to organize dueling pro- and anti-Trump rallies near each other at the same time in hopes of provoking violence. They did not care which side got blamed.

The rabbit hole goes deep. When Clinton and others started pinning Trump’s victory on imaginary collusion with the Russians, the Russians joined-in! They advanced the conspiracy theory because it would erode public trust in the electoral system. It is one of the great ironies of modern American politics: Those who claim that Trump was put in office by Russian disinformation are themselves parroting Russian disinformation.

Trump was subject to a lengthy investigation by an independent special council—Robert Mueller. He found no evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia. And yet, even now, Clinton periodically makes public comments implying that Trump was a Russian asset installed by foreign collusion. She and her ilk will deny the fairness of the 2016 results, then moments later condemn anybody who questions the 2020 results as an “election denier” and traitor. Curious.

Trump’s Presidency

Trump became the president at noon eastern time on January 20, 2017. Thus began a very strange four years.

Trump was as “Trumpy” as ever—he still made weird Twitter posts at odd hours, said bizarre and sometimes incoherent things, and brought a lot of absurdity and distraction into the White House. His close advisors in the West Wing indulged his worst instincts, but most of his cabinet nominees were solid professionals who did good work. Economic and regulatory policies in the executive branch improved rapidly, as did foreign policy regulations relating to the right to life and freedom of religion. Border policies were tightened up, including provisions that made drug and sex trafficking more difficult.

In terms of actual quality-of-life, things went very well in Trump’s first three years . . . if you looked past all the noise and nonsense. The economy was the strongest it had been in decades, partly thanks to lower taxes and reduced regulatory burdens. We were not deeply embroiled in major world conflicts. There was a constant churn of public controversies involving Trump, but they were mostly distractions based on dumb comments or Tweets, blown far out of proportion, or entirely manufactured. There are two major exceptions.

The Mueller Report

In early 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions (R) recused himself from investigations relating to Russian election interference. He had met with Russian officials as a U.S. Senator, which was innocuous, but because he was a Trump campaign “surrogate” at the time it raised questions about impartiality. Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein (R) thus became the “acting attorney general” in relation to 2016 election investigations. On May 17, 2017, Rosenstein appointed former FBI Director Robert Mueller (R) to continue investigating “Russiagate” as an independent special council.

The “Mueller report,” or Report on the Investigation into Russian Interference in the 2016 Presidential Election, was released to the public (with redactions) on April 18, 2019. The first volume included a detailed review of Russian efforts to interfere in the 2016 presidential election. It concluded that there was no collusion between Russia and the Trump campaign; no charges were warranted against Trump or anybody connected with his campaign. Several Trump associates were, however, charged for lying “about their interactions with Russian-affiliated individuals and related matters.” As the old political maxim goes, “The cover-up is worse than the crime.”

The second volume of the “Mueller report” was an embarrassing cop-out. Mueller implied that Trump may have obstructed justice, but he refused to come to any clear conclusions and refused to make prosecutorial recommendations. I ended up having to do his job for him. Read that article for details, but, in summary, Trump might have broken the law by trying to get White House Counsel Don McGahn, former campaign manager Paul Manafort, and former Trump attorney Michael Cohen to lie to or mislead investigators (see Volume II, Section II, Parts I, J, and K respectively).

In all three cases, the evidence was insufficient to warrant impeachment, let alone conviction. With McGahn, it cannot be proved that an obstructive act even occurred—it’s McGahn’s word against Trump’s. I suspect McGahn is telling the truth, and that Trump broke the law, but there is no way to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt. With Manafort and Cohen, the alleged acts occurred, but whether they constituted obstruction would depend on what Trump intended by them (because they were not intrinsically criminal). There is not enough circumstantial evidence to establish beyond a reasonable doubt that Trump had a criminal intent.

Ukraine Scandal

The second “real” controversy of the Trump presidency (before 2020) relates to an alleged abuse of power in relation to the Biden family and Ukraine. To understand these events, we must briefly review the situation in Ukraine during the 2010s. This will be an oversimplification, but it will provide a “sense” of what was happening.

There were two major factions in Ukrainian politics. One, led by the Fatherland Party, favored closer relations with the European Union (E.U.). The other, led by the Party of Regions, favored closer relations with Russia. The Fatherland Party tended to be more popular in western regions (i.e., closer to Europe) and the Party of Regions in the east (i.e., closer to Russia). In the 2010 Ukrainian presidential election, Viktor Yanukovych (Party of Regions) defeated Yulia Tymoshenko (Fatherland Party), putting the Ukrainian government on a more pro-Russian trajectory.

In November 2013, a series of large-scale public protests broke out in response to Yanukovych’s decision not to sign a previously approved association and free-trade agreement with the E.U. These came to be known as “Euromaidan” or the “Maidan Uprising,” named for Independence Square—Maidan Nezalezhnosti—in Kyiv. Unrest soon grew into a full-scale revolt—the “Revolution of Dignity” or “Ukrainian Revolution”—and the clashes between the government and protestors threatened to spiral into civil war.

The Ukrainian parliament convened an emergency session on February 22, 2014. It had 450 members, but only 328 were present. They voted unanimously to remove Yanukovych from office. There was no provision under the Ukrainian constitution to remove a president except through impeachment and conviction, which would have required the support of three-quarters of the total membership. That means they needed 338 votes; there weren’t even that many members there. This was a coup-d’etat.

President Barack Obama (D) threw the weight of American diplomacy behind the coup. Efforts to bolster the new government were led by then-Vice President Joe Biden (D). At the same time, Joe Biden’s son—Hunter Biden—was hired by Ukrainian energy firm Burisma to serve on its board. Hunter Biden had no experience in energy, business, or anything else that would make him a likely candidate to serve in this role. The corrupt head of Burisma, Mykola Zlochevsky, almost certainly hired Hunter Biden to establish a “back door” connection to Obama. Hunter Biden almost certainly knew that. He’s a sleaze. There is little evidence that Joe Biden solicited or intentionally participated in his son’s corrupt dealings.

Zlochevsky and Burisma were subject to an investigation by Ukraine’s prosecutor general’s office for alleged money laundering and tax evasion; when Viktor Shokin became prosecutor general in 2015, he inherited those investigations. Western governments pushed for Shokin’s ouster because, they claimed, he was corrupt too (and he was). Shokin was fired in March 2016, and Joe Biden later took credit for it when he bragged, “I looked at them and said, I’m leaving in six hours. If the prosecutor is not fired, you’re not getting the money. Well, son of a bitch, he got fired.”

In March 2019, Ukrainian voters put Volodymyr Zelenskyy—a comedian and actor—in office as president of the post-coup government. In the United States, Hunter Biden’s connections to Ukraine had bubbled to the surface and were getting attention.

President Trump spoke to Zelenskyy by phone on July 25, 2019. Trump asked for a new investigation into Burisma, Hunter Biden, and the firing of Shokin, and implied that foreign aid to Ukraine could be reduced if they didn’t do it. Whistleblowers claimed this was a corrupt “quid-pro-quo” arrangement, but Trump and Zelenskyy each denied understanding it that way. Even if it was a “quid-pro-quo,” it wasn’t necessarily “corrupt.” Hunter Biden’s employment at Burisma warranted investigation, and using foreign aid to pressure foreign governments to act is perfectly normal. “Well, son of a bitch,” just ask Joe Biden.

Trump was eventually impeached for “abuse of power” and “obstruction of Congress” in relation to the July 25 call. House investigators alleged that Trump solicited foreign interference in the 2020 election to undermine a likely opponent, Joe Biden, who was then running for the Democratic nomination. This accusation was factually inaccurate . . . Trump had asked Ukraine to investigate Hunter Biden, who is not the same person as Joe. The “obstruction of Congress” accusation was procedurally invalid because Congress had not challenged Trump’s refusal to cooperate with subpoenas with the Supreme Court, which would have been a prerequisite for an impeachment. Trump was acquitted on both counts.

Election 2020

I recount everything described above because it helps describe the world as it existed as we stepped into the 2020 election season.

President Trump was probably on track for a relatively easy win. Despite all the controversy and distractions, things were going well. The economy was strong, and that is usually one of the strongest predictors of whether a president will be reelected. When stocks and 401ks are way up, and the unemployment and inflation rates are low, incumbents usually win. And the Democratic Party had no stars waiting in the wings to challenge Trump. Biden was essentially nominated by default; he was “next in line” and no other candidates had generated enough buzz to pull ahead.

The election was destined to be . . . weird. Elections involving Trump always are. Race riots had occurred in numerous major cities throughout 2020, and Democratic Party figures had adopted one of the dumbest political slogans in modern history: “Defund the police.” Biden was smart enough not to repeat it himself, but some voters understandably lumped him in with his party’s more vocal wackos. And it didn’t help that the election was a pitched battle between two aged septuagenarians.

But if that didn’t set a strange enough stage, there was a surprise brewing in Wuhan, China. A mysterious respiratory illness had sprung up in November 2019 (or possibly earlier; the official timeline is not trustworthy). The Chinese government attempted to cover it up, and the World Health Organization helped, so we lost any chance to contain this novel coronavirus before it exploded into an unprecedented pandemic. The virus was later christened “SARS-CoV-2” and the illness it caused was named “COVID-19.”

COVID-19

The overreaction to COVID-19—which was serious, but not the apocalyptic calamity it was made out to be—enflamed all the existing political tensions. Although Republican leaders at the state level tended to adopt more rational policies than their Democratic counterparts, the federal authorities—under Trump—soon flew far off the rails. This reduced support for Trump among conservatives and right-leaning moderates. The damage done to the national and world economies by insane, misguided COVID-19 policies also reversed much of Trump’s previous advantage there. The pandemic, and the world’s reaction to it, turned an easy Trump win into a tied race.

As we approached the election, many state governments maintained bizarre and unnecessary policies—widespread public masking requirements, discouraging large gatherings, and more. None of this made any sense anymore (and little of it made sense even when the pandemic was a more serious threat months earlier). Many voters who might normally have voted in person on election day chose instead to take advantage of early, by-mail, and absentee voting policies. Many states also expanded the availability of these options—removing requirements, offering more early voting times and locations, and so on—which likely encouraged some people to vote who might not have bothered in other years.

This sort of thing tends to benefit Democrats. Republicans are statistically more likely to care about voting and go out of their way to do it, so making voting “easier” tends to have little effect on Republicans but increases Democratic turnout. Those votes are, of course, still legitimate . . . even if the motives for the policy changes aren’t pure.

In any case, absentee voting is less secure and more prone to fraud and abuse. When people shift from verified in-person voting to un-verified absentee voting, that increases the likelihood of cheating. It is obviously easier to cheat when identities are not verified and there is not even a need to be physically present in a public space to fill out a ballot. This contributed to some Trump supporters’ doubts about the validity of the election results.

There is no evidence that there was enough of this fraud to change the outcome of the race. I only question the results when it is known that significant numbers of invalid votes were included in the results, which is the case only in Pennsylvania, where mail-in ballots received long after the state’s constitutional deadline are known to have been counted and included in the results.

Election Day

November 3, 2020, was election day . . . but a significant percentage of the votes had already been cast days, weeks, or even months earlier. Many Americans were still spooked by continued fearmongering about COVID-19 by health officials and the media, so they took advantage of expanded access to less secure voting methods.

The people who showed up to vote in person on election day tended to be those who were not particularly concerned about catching the mostly harmless variants of COVID-19 then circulating. For reasons long predating the pandemic, Republican voters tend to distrust government officials and the press, and Democratic voters tend to believe them. It follows that a disproportionate percentage of mail-in and early votes came from Biden supporters, and a disproportional percentage of in-person votes on election day came from Trump supporters.

Many states, including Virginia, count the in-person votes first. Election commentators (like me) expected early results to be skewed in Trump’s favor, then shift back toward Biden as the early and absentee votes got counted afterwards. In states where absentee votes could be received and counted after election day, this shifting of the results toward Biden could continue for up to a week. That’s why it took so long to call some states and determine who won.

There were not many real surprises in the results. Most states landed close to where pollsters and analysts expected them to. The oddities we have heard so much about—like late night “vote dumps” where the numbers seemed to leap in Biden’s favor all at once—were the result of the unusual nature of the election. Those were the early and absentee ballots getting added to the results. We knew they would come after the in-person ballots. We knew they would be more numerous than usual. We knew they would skew heavily in Biden’s favor. It would have been more suspicious if we didn’t see big shifts to Biden as those ballots got counted and added to the results.

In the end, Biden won 306 electors to Trump’s 232. There were no “faithless electors.” Biden also won the national popular vote by about five percentage points, or 7.06 million votes.

Denial

Almost immediately, Trump and his partisans alleged that the presidential race had been “stolen” by election fraud and other shenanigans in several “swing” states. Most of these claims were rooted in ignorance about how elections work—like the order in which ballots are counted. Some of them were outright lies. Some of the claims had merit, or at least raised legitimate questions, but none on a large enough scale to have changed the result.

There is one exception that must be acknowledged . . . one that got relatively little attention from Trump or his supporters. Pennsylvania’s election laws require that mail-in and absentee ballots be received by 8:00 p.m. on election day, but state officials declared that ballots received after that deadline would still be counted. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court upheld this, and the U.S. Supreme Court declined to intervene. This was a direct violation of Pennsylvania state election law, and, by extension, the U.S. Constitution, which gives authority to choose the times, places, and manner of conducting elections not to election officials or state courts, but to the state legislatures.

It is very likely that Biden would have won Pennsylvania anyway—the total number of ballots received after the deadline was less than his margin of victory—but the state’s decision to include known illegal ballots means we can’t trust the result. The numbers are known to be incorrect. How many other election laws did they decide not to obey that week?

If Pennsylvania’s electors had gone to Trump, he still would have lost. At least one other state would have to change its results too, and there aren’t any where there is proof of enough fraud to have made a difference or where, like in Pennsylvania, the whole result was poisoned by blatant illegality. There are isolated irregularities, sure—as there are in every election—but nothing systemic. Trump and his supporters can assert that the election was stolen all they want, but nobody should believe them unless they can show us proof. Not just innuendos and isolated oddities . . . proof. They haven’t.

The Capitol Riot

On January 6, 2021, the United States Congress gathered in joint session for the purpose of counting the states’ electoral votes and certifying Joe Biden as the winner of the presidential election. Then-Vice President Mike Pence (R), in his role as the president of the U.S. Senate, presided.

Trump had spent almost two months spreading the false claim that he had won the election, and many of the more credulous Trump voters believed him. He and his team planned a “March to Save America” rally on the National Mall, where several Trump-connected officials—and Trump himself—would speak to supporters and then march together in protest to the U.S. Capitol.

Electoral Counts

The President of the United States is elected through a unique, indirect process. Each state is allotted the number of electors equal to the size of their total congressional delegation—members in the House and Senate. Another three electors are allotted to the District of Columbia.

Most states allot their electors as a “slate” to the presidential candidate who wins the plurality of the state’s vote; for example, Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election in Virginia (about 54-44%), so all thirteen of Virginia’s electors went to Biden. Some states use the “congressional district method,” which allots two electors (corresponding to the state’s two senators) to the winner of the statewide vote, and the remaining electors (corresponding to each of the state’s congressional districts) to whichever candidate receives the most votes in that district.

To be elected president, a candidate must receive an outright majority of the electoral college vote. There are 538 electors, so a candidate must receive at least 270 votes to win. If no candidate achieves an electoral college majority, the House of Representatives selects a president with a “majority of the states” vote.

Each state transmits the outcome of its electoral vote to Congress, which counts the votes and certifies the national results. Members of Congress may raise objections to a state’s vote; if an objection is has the support of at least one member in each of the two houses, it must be debated and then adopted or rejected by vote. Objections are rare, but they do happen. Then-Senator Barbara Boxer (D-CA) and then-Representative Stephanie Tubbs Jones (D-OH 11th) objected to counting Ohio’s vote to reelect President George W. Bush (R) in 2004 (the objection was rejected and Ohio’s votes were counted). Congress has never voted to uphold any such objection. If it ever did, it would raise serious constitutional questions . . . state legislatures have the authority to govern how a state’s electoral votes are allotted and cast, and Congress has no clear authority to second-guess what they do.

Nonetheless, Republicans planned to raise objections to several states’ votes in 2021. Trump and others also asserted that Pence, who presides over the proceeding as president of the Senate, had the authority to unilaterally toss-out a state’s electoral count.

Pence told Trump that he had no such authority, and that any attempt to throw out a state’s vote would be unconstitutional. Minutes before Congress gathered to count the votes, Pence posted a message on Twitter saying, “It is my considered judgment that my oath to support and defend the Constitution constrains me from claiming unilateral authority to determine which electoral votes should be counted and which should not.” Speaking about this in 2023, Pence said, “The Constitution affords no authority—to the vice president or anyone else—to reject votes or return votes to the states.”

He’s right.

Timeline of Events

The “March to Save America” began at 9:00 a.m. on January 6, 2021, at the Ellipse—a large park just south of the White House. Trump was at the White House making phone calls as the rally started, including a 26-minute call with speechwriter Stephen Miller to finalize the text of the speech Trump would later give.

Between 10:30 and 11:00 a.m., hundreds of members of the Proud Boys, a radical group often characterized as “far-right” or “neo-fascist,” left the rally at the Ellipse and headed toward the Capitol.

Trump took the stage at 11:57 a.m. and spoke for over an hour. He claimed he would walk with his supporters to the Capitol where they could “peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard.” Meanwhile, over a mile away, the Proud Boys and a rowdy crowd of Trump supporters were gathering at the Capitol’s security barricades. At 12:53 p.m.—nineteen minutes before Trump finished his speech—the crowd first breached the perimeter and began flooding onto the Capitol grounds.

Within five minutes of the breach, Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund asked House Sergeant-at-Arms Paul Irving and Senate Sergeant-at-Arms Michael Stenge to declare an emergency and call out the National Guard. They refused. Sund repeated his request for reinforcements at least four more times over the following hour, but was rebuffed. Rioters were on the grounds and fighting with Capitol Police but had not yet entered the building.

At 1:00 p.m., Pence and members of the U.S. Senate walked to the House chamber to start the joint session and begin counting electoral votes. Trump was still speaking at the Ellipse; he finally wrapped-up at 1:10 p.m., and his motorcade departed the rally at 1:17 p.m. Trump later told journalist Jonathan Karl that he intended to go directly to the Capitol, but his U.S. Secret Service detail, who were monitoring the deteriorating situation, took Trump back to the White House instead. At the Capitol, soon after the process began, some members objected to counting Arizona’s votes. Pence and the Senators returned to their own chamber so the houses could debate the matter separately.

Many Trump supporters who had stayed at the Ellipse for Trump’s entire speech were starting to make their way down Pennsylvania Avenue to the Capitol, where, at the same time, rioters continued pushing back the Capitol Police. By 1:30 p.m., police had retreated to the building. At 1:49 p.m., apparently no longer willing to wait for Irving and Stenge to do their jobs, Chief Sund contacted the D.C. National Guard directly and requested assistance. Major General William Walker began preparations, but needed permission from the Secretary of the Army before he could deploy. That permission was not given for more than an hour.

At 1:59 p.m., rioters reached the doors of the U.S. Capitol and started trying to break in. At 2:10 p.m., Irving finally woke up and authorized Sund to request National Guard assistance (which he had done ten minutes earlier without formal authorization). Two minutes later, the first rioter breached the U.S. Capitol through a broken window and opened a door. Hundreds more started flooding into the building. Within a minute of the breach, the U.S. Secret Service removed Pence from the Senate chamber and the Senate was gaveled into recess. Less than ten minutes after that, Representative Nancy Pelosi (D-CA 12th), then Speaker of the House, was evacuated from the House chamber and the House was also gaveled into recess.

At 2:24 p.m., Trump posted on Twitter: “Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our Country and our Constitution, giving States a chance to certify a corrected set of facts, not the fraudulent or inaccurate ones which they were asked to previously certify. USA demands the truth!” According to a House committee report on the events of January 6, “Immediately after this tweet, the crowds both inside and outside of the Capitol building violently surged forward.” Chaos now reigned; rioters were moving through the building, threatening officials, and vandalizing or stealing whatever they found.

At 2:39 p.m., Trump made another post on Twitter: “Please support our Capitol Police and Law Enforcement. They are truly on the side of our Country. Stay peaceful!”

A rapid series of events occurred over the ten-minute period beginning around 2:40 p.m. The vice president and many members of the House and Senate were holed-up in secure locations while rioters walked through Capitol complex hallways chanting slogans and banging on office doors. At 2:42, rioters entered the Senate chamber. At 2:44, rioter Ashli Babbitt attempted to force her way into a secure area where members were being guarded and was shot and killed by a Capitol Police officer. Around the same time, rioters reached the House chamber but were turned back by locked doors and armed officers. Other rioters broke into Pelosi’s office and ransacked it.

At 3:04 p.m., Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy finally approved the call-up of the D.C. National Guard. Virginia National Guard assets also started entering the district within fifteen minutes in response to an order by then-Governor Ralph Northam (D), though a federal authorization for “out-of-state” National Guard support in the district was not granted until 5:45 p.m.

At 3:13 p.m., Trump posted another message on Twitter: “I am asking for everyone at the U.S. Capitol to remain peaceful. No violence! Remember, WE are the Party of Law & Order – respect the Law and our great men and women in Blue. Thank you!” The riot continues unabated.

At 4:17 p.m., Trump posted a bizarre video on Twitter. It was one of several extemporaneous recordings he had made over a ten-minute period. His aides thought this one was the least objectionable option:

I know your pain, I know you’re hurt. We had an election that was stolen from us. It was a landslide election and everyone knows it, especially the other side. But you have to go home now. We have to have peace. We have to have law and order. We have to respect our great people in law and order. We don’t want anybody hurt. It’s a very tough period of time. There’s never been a time like this where such a thing happened where they could take it away from all of us—from me, from you, from our country. This was a fraudulent election, but we can’t play into the hands of these people. We have to have peace. So go home. We love you. You’re very special. You’ve seen what happens. You see the way others are treated that are so bad and so evil. I know how you feel, but go home, and go home in peace.

The first D.C. National Guard forces arrived at the Capitol around 5:40 p.m. The process of clearing rioters from the building and securing the Capitol began in earnest. D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser (D) declared an emergency curfew that came into effect at at 6:00 p.m.

At 6:01 p.m., Trump posted another message on Twitter: “These are the things and events that happen when a sacred landslide election victory is so unceremoniously & viciously stripped away from great patriots who have been badly & unfairly treated for so long. Go home with love & in peace. Remember this day forever!”

By 6:30 p.m., the Capitol was nearly empty. Law enforcement officials said they were confident the building would be secure within an hour, and finally declared it so at 8:00 p.m. Congress reconvened at 8:06 and restarted the vote-counting process. There were several more challenges and debates, but they finally certified the results at 3:32 a.m. on January 7.

On Conspiracy

Three of the four charges in this indictment allege that Trump engaged in conspiracies. I must repeat some of what I wrote in my analysis of Trump’s federal documents charges, where Trump was accused of committing a “Conspiracy to Obstruct Justice.” If you have already read that article, you can probably skip this section.

A “conspiracy” occurs when a group of people plan to work together to commit other crimes. It is a crime in-and-of itself, separate from the crimes they are conspiring to commit. “For example, one who conspires with another to commit burglary and in fact commits the burglary can be charged with both conspiracy to commit burglary and burglary” (Batten 2010, “conspiracy”).

Alleged conspirators can also be charged even if they never went through with the crime they were planning. “It does not matter whether the crime itself is ever performed or attempted. Nor does it matter if one participant has no intention to commit the crime; as long as the participant plans or works with at least one other person in support of the supposed future criminal act, that participant is conspiring to commit the crime” (Sheppard 2012, “conspiracy”). Once a conspiracy exists, “conspirators are liable for all crimes committed within the course or scope of the conspiracy” (Batten 2010, “conspiracy”).

The notion of “conspiracy” as a standalone crime is problematic. Its justification is that “when two or more persons agree to commit a crime, the potential for criminal activity increases, and as a result, the danger to the public increases” (Batten 2010, “conspiracy”). Perhaps. But we cannot categorize everything that might increase “danger to the public” as a crime; that would open a strange and dangerous can of worms. We’re getting into “thoughtcrime” territory here. Sure, if I think about robbing a bank it may increase the likelihood that I’ll eventually do it. I thought about it while I was writing that sentence. Now I’ve told you about it. Welcome to my conspiracy.

The crime of “conspiracy” is also far too vague. In his concurring opinion in Krulewitch v. U.S. (1949), U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Robert Jackson said that conspiracy is an “elastic, sprawling[,] and pervasive offense” that is “so vague that it almost defies definition” (Garner 2019, “conspiracy”). Some legal experts believe that “the allegation of conspiracy is used by prosecutors as a superfluous criminal charge. . . .” Prosecutors and defense attorneys broadly agree that “conspiracy cases are usually amorphous and complex” (Batten 2010, “conspiracy”).

Under the due-process clauses of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments, laws that are not clearly defined are void for vagueness (Garner 2019, “void—void for vagueness”). A law must be invalidated if it does not provide “the kind of ordinary notice that will enable ordinary people to understand what conduct it prohibits,” or if “it may authorize and even encourage arbitrary and discriminatory enforcement” (Sheppard 2012, “Vagueness Doctrine”).

Conspiracy laws belong in this category. How is the average citizen supposed to determine when the consideration or discussion of a crime crosses the line from idle chit-chat to criminal conspiracy? The presence of “criminal intent” is the main legal trigger, but what is that specifically, and how is it proved?

Despite erroneous precedent to the contrary, planning a crime simply cannot be a crime in and of itself. If conspirators never move forward with the plot, no harm has been done and there is no reason to charge anybody with anything. If they do go ahead with it, they should be charged with whatever crimes they end up committing (or attempting to commit). The only valid purpose for “conspiracy” laws is to ensure that all members of a conspiracy are held accountable for crimes committed in furtherance of it.

Alleged Offenses

Prosecutors acknowledge that Trump “had a right, like every American, to speak publicly about the election and even to claim, falsely, that there had been outcome-determinative fraud during the election and that he had won,” but also allege that he “pursued unlawful means of discounting legitimate votes and subverting the election results” with three overlapping conspiracies:

- “A conspiracy to defraud the United States by using dishonesty, fraud, and deceit to impair, obstruct, and defeat the lawful federal government function by which the results of the presidential election are collected, counted, and certified by the federal government . . . ” (count 1),

- “A conspiracy to corruptly obstruct and impede the January 6[, 2021,] congressional proceeding at which the collected results of the presidential election are counted and certified . . . ” (count 3), and

- “A conspiracy against the right to vote and to have one’s vote counted . . . ” (count 4).

Prosecutors say that “each of these conspiracies—which built on the widespread mistrust the Defendant was creating through pervasive and destabilizing lies about election fraud—targeted a bedrock function of the United States federal government: the nation’s process of collecting, counting, and certifying the results of the presidential election.” The alleged “criminal scheme” to overturn the election began, prosecutors claim, “shortly after election day.”

In addition to the alleged conspiracies, Trump is also accused of obstructing an official proceeding with his actions on January 6, 2021, relating to the electoral vote certification (count 2).

The detailed accusations are listed in the indictment under count 1 and incorporated by reference under the other charges. Prosecutors claim the purpose of the alleged conspiracies was to “overturn the legitimate results of the 2020 presidential election by using knowingly false claims of election fraud to obstruct the federal government function by which those results are collected, counted, and certified.”

Six numbered, but unnamed, co-conspirators are listed in the indictment.

Five examples of the “manner and means” of the conspiracies are listed. Prosecutors allege that Trump and his co-conspirators:

- “Knowingly [made] false claims of election fraud to get state legislators and election officials to subvert the legitimate election results and change electoral votes . . . ,”

- “Organized fraudulent slates of electors in seven targeted states . . . ,”

- “Attempted to use the power and authority of the Justice Department to conduct sham election crime investigations . . . ,”

- “Attempted to enlist the Vice President to use his ceremonial role at the January 6 certification proceeding to fraudulently alter the election results . . . ,” and

- “Exploited the disruption [of the Capitol riot] by redoubling efforts to levy false claims of election fraud and convince Members of Congress to further delay the certification. . . .”

Prosecutors believe Trump knew his claims about the election were false. They present evidence that he was “notified repeatedly that his claims were untrue—often by the people on whom he relied for candid advice on important matters, and who were best positioned to know the facts—and he deliberately disregarded the truth.”

The indictment cites numerous examples of acts that allegedly furthered the conspiracies. These acts were directed at state officials in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin; at Department of Justice officials; and at Vice President Pence. It also includes an allegation that Trump and his co-conspirators exploited the “violence and chaos at the Capitol” by trying to further delay the certification vote.

The Charges

The remainder of this post is a review of the four specific charges contained in the indictment.

Against the Election (Count 1)

One count of the indictment (count 1) charges Trump with “Conspiracy to Defraud the United States” in violation of 18 USC § 371.

Prosecutors accuse Trump and other “co-conspirators, known and unknown to the Grand Jury” of engaging in a conspiracy to “defraud the United States by using dishonesty, fraud, and deceit to impair, obstruct, and defeat the lawful federal government function by which the results of the presidential election are collected, counted, and certified by the federal government.”

The Law

This charge is made under United States Code, Title 18, Section 371, “Conspiracy to commit offense or to defraud United States.” The section reads:

If two or more persons conspire either to commit any offense against the United States, or to defraud the United States, or any agency thereof in any manner or for any purpose, and one or more of such persons do any act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than five years, or both. . . .

Analysis

In this count, prosecutors allege that Trump and his co-conspirators engaged in a conspiracy designed to obstruct a legitimate government function—the collection, counting, and certification of presidential electoral votes in accordance with the U.S. Constitution (Article II, Section 1 and 12th Amendment) and the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (3 USCS §§ 5-7 and 15-18).

As is the case with most federal conspiracy laws, section 371 is extremely vague and open-ended. It prohibits any conspiracy that is intended to “commit any offense against,” or “defraud,” the United States or any U.S. government agency.

The statute itself contains fewer than one hundred words . . . but there are over 1,300 pages about it in Thomson Reuters’s United States Code Annotated (USCA 2023, § 371) and over 650 in LexisNexis’s United States Code Service (USCS 2023, § 371). It would be impossible to perform a thorough analysis of all the case law relating to this section; we must “make do” with a more cursory look.

The indictment does not describe any specific violation of law—an “offense”—that the conspirators allegedly intended to commit; the closest it comes is vaguely citing the U.S. Constitution and the Electoral Count Act. Based on this, and the title given for this section of the indictment, it appears that prosecutors are accusing Trump of an intent to defraud the United States.

As I explained in my analysis of Trump’s New York business documents indictment, to defraud is “to cause injury or loss to (a person) by deceit” (Garner 2019, “Defraud”) or “to deprive of something by fraud,” which is “a misrepresentation or concealment with reference to some fact material to a transaction . . . with the intent to deceive another . . . who is injured thereby” (M-W Law 2023, “Defraud” and “Fraud”). Being defrauded means that a victim has been injured in some way—they have been deprived of something to which they have a right. In both common and legal usage, “defraud” normally applies to money and property. It can occasionally apply to other rights.

As it relates to section 371, courts have often interpreted the term “defraud” very broadly. The law supposedly “not only reaches schemes that deprive government of money or property,” but also “covers acts that interfere with or obstruct lawful governmental functions” (USCS 2023, § 371 “Conspiracy to defraud United Status”). There are cases where courts applied it more narrowly; in U.S. vs. Caldwell (1993) the court ruled, “Obstructing government functions by violence, robbery, or advocacy of illegal action is not ‘defrauding’ within [the] meaning of [the] statute” (USCA 2024, § 371 “Defrauding United States”).

As I said in the business documents case, “Laws should be interpreted under their plain meaning—how they would be commonly understood at the time they were adopted. The plain meaning of the term ‘defraud’ is to use deceit to cause somebody a loss, especially, but not exclusively, in money or property. Depriving somebody of other rights could be defrauding them, but only in very direct and obvious cases. To establish an intent to defraud, we must clearly establish who was the intended victim and what they were going to be deprived of.”

Prosecutors have not explained how Trump’s alleged conspiracy would “defraud” anybody. No examples of fraud are given except for the claim that Trump intended to interfere with lawful government activity, which does not fall within a plain text reading of the law . . . case-law to the contrary notwithstanding.

Conclusion

For the reasons described in the “Background” section under the subheading “On Conspiracy,” the “Conspiracy to Defraud the United States” charge (count 1) is morally and constitutionally invalid. Trump should be acquitted.

Even if this were not the case, the conditions of the charge under a plain-text interpretation of section 371 are not met. Prosecutors allege that Trump and unnamed conspirators intended to “defraud the United States,” but they have failed to explain who was to be defrauded of what. Courts have sometimes interpreted the word “defraud” in this statute to include any interference with lawful government functions, but that violates the basic principle that laws must mean what they say . . . because that’s not what the law says.

If we accepted the argument that Trump was attempting to unlawfully interfere with the electoral count—which has not been proved—it still would not constitute fraud under this section. It could possibly be prosecuted under this section’s clause prohibiting conspiracies to “commit any offense against the United States,” but prosecutors would have to describe what the supposed offense was and what section of the United States Code prohibits it. They haven’t done so.

Against a Proceeding (Counts 2-3)

Two counts of the indictment (counts 2 and 3) charge Trump with “Conspiracy to Obstruct an Official Proceeding” and “Obstruction of, and Attempt to Obstruct, an Official Proceeding” in violation of 18 USC § 1512.

Under count 2, prosecutors accuse Trump and other “co-conspirators, known and unknown to the Grand Jury” of engaging in a conspiracy to “corruptly obstruct and impede an official proceeding, that is, the certification of the electoral vote, in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 1512(c)(2),” which would itself violate 18 USC § 1512(k).

Under count 3, prosecutors accuse Trump of attempting to “corruptly obstruct and impede an official proceeding, that is, the certification of the electoral vote” in violation of 18 USC § 1512(c)(2) and 18 USC § 2.

The Law

Counts 2 and 3 both fall under United States Code, Title 18, Section 1512, “Tampering with a witness, victim, or an informant.” Count 2 refers to subsection (k), which reads:

Whoever conspires to commit any offense under this section shall be subject to the same penalties as those prescribed for the offense the commission of which was the object of the conspiracy.

The specific crime that Trump allegedly conspired to commit is under subsection (c)(2), which is the same subsection he is accused of violating in count 3. That subsection reads:

Whoever corruptly . . . obstructs, influences, or impedes any official proceeding, or attempts to do so, . . . shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 20 years, or both.

Count 3 also cites United States Code, Title 18, Section 2, “Principals,” which reads:

(a) Whoever commits an offense against the United States or aids, abets, counsels, commands, induces[,] or procures its commission, is punishable as a principal.

(b) Whoever willfully causes an act to be done which if directly performed by him or another would be an offense against the United States, is punishable as a principal.

This section establishes a principle that inducing or causing somebody else to commit a federal crime can be prosecuted as if they had committed it themselves. It serves as a sort-of “catch-all” that allows prosecutors to hold defendant responsible for things he may have caused others to do on his behalf.

Analysis

In count 2, prosecutors allege that Trump and his co-conspirators engaged in a conspiracy designed to impede an official proceeding—the collection, counting, and certification of presidential electoral votes in accordance with the U.S. Constitution (Article II, Section 1 and 12th Amendment) and the Electoral Count Act of 1887 (3 USCS §§ 5-7 and 15-18).

The charge is under section 1512(k), the same subsection under which he was charged with conspiracy in count 33 of the federal documents case. Much of the analysis described there (and in the “On Conspiracy” section above) applies.

In count 3, prosecutors accuse Trump of attempting to actually impede the official proceeding, as opposed to just conspiring to do it. It makes the most sense to consider count 3 before count 2, since count 3 speaks to the alleged underlying crime that was the subject of the alleged conspiracy in count 2.

To be convicted on count 3, prosecutors would have to prove:

- The electoral count was an official proceeding,

- Trump intended to obstruct or impede it, and

- That intent was corrupt.

On the first point, that’s pretty much indisputable. Yes, the electoral count was an official proceeding.

Things get a lot murkier on the second and third points. Trump was attempting to affect the electoral count by delaying it, causing some states’ electors to be disqualified, or causing Vice President Pence to unilaterally reject some states’ electors, but it’s not clear that affecting an official proceeding is obstructing an official proceeding.

Calling on members of Congress or on Pence to delay the electoral count is not obstruction; anybody can ask Congress to do or not do something as long as they don’t do anything to stop them (more on that later).

Calling on members of Congress to challenge some states’ electors is not obstruction either. A process exists for exactly that purpose; it had been used before 2020 and is likely to be used again in the future.

And calling on Pence to reject electors in his role as President of the Senate isn’t obstruction. It’s a request based on an erroneous understanding of the vice president’s role in the proceeding, but we don’t prosecute people for misunderstanding or misinterpreting how a proceeding works.

It’s obvious that legislators did not intend for this law to be used in these kinds of situations . . . because, if they did, every president and many other public officials would be subject to constant prosecution for daring to ask Congress to do stupid things.

If these actions serve as the basis of the charge, it would also be impossible to prove corrupt intent. It is possible that Trump really believed he won the election and it had been stolen from him. If so, his efforts to influence the electoral count would be, in his mind, efforts to save the democratic process, not to undermine it. If that’s the case, then he was just an idiot. Being wrong isn’t a crime. Prosecutors allege that Trump knew he lost, and cited as evidence the fact that many of his trusted advisors told him so, but it is (obviously) possible to believe things that all the people around you don’t believe . . . especially if you’re a strange sort of person.

The strongest argument that Trump’s actions constituted corrupt obstruction of an official proceeding would require us to hold him responsible for the Capitol riot . . . but we’ve been over that before; Trump did not incite it and bears no legal responsibility for it.

Other people might be chargeable under this section for what happened on January 6, but the attack was already underway while Trump was giving his rambling speech at the Ellipse and calling for a peaceful march to the Capitol. There is no causal relationship between Trump’s actions and the riot. Even if there was, here, too, it would be difficult to prove corrupt intent. Trump might have believed that he had won the election and drastic action was necessary. Again, dumb, but not illegal.

This same logic applies to the conspiracy charge. It’s not clear that the alleged conspiracy was meant to obstruct an official proceeding at all, and, even if it was, it’s not clear that there was any corrupt intent.

Conclusion

For the reasons described in the “Background” section under the subheading “On Conspiracy,” the “Conspiracy to Obstruct an Official Proceeding” charge (count 2) is morally and constitutionally invalid. Trump should be acquitted.

Even if this were not the case, it has not been proved beyond a reasonable doubt that the alleged conspirators intended to unlawfully obstruct a proceeding (as opposed to just influencing it), or that they had corrupt intent.

The “Obstruction of, and Attempt to Obstruct, an Official Proceeding” charge (count 3) cannot be proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Trump should be acquitted.

Trump was clearly attempting to influence a Congressional proceeding—the electoral vote count—but that does not constitute obstruction. Even if it did, it cannot be proved that Trump had corrupt intent. He might have believed that his actions would correct an otherwise improper proceeding.

If it could be proved that Trump incited or caused the Capitol riot, prosecution under this section could be appropriate, but there was no provable causal relationship between anything Trump did and the riot that occurred at the Capitol.

Against the People (Count 4)

One count of the indictment (count 4) charges Trump with “Conspiracy Against Rights” in violation of 18 USC § 241.

Prosecutors accuse Trump and other “co-conspirators, known and unknown to the Grand Jury” of engaging in a conspiracy to “injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate one or more persons in the free exercise and enjoyment of a right and privilege secured to them by the Constitution and laws of the United States—that is, the right to vote, and to have one’s vote counted” in violation of 18 USC § 241.

The Law

This charge is made under United States Code, Title 18, Section 241, “Conspiracy against rights.” The section reads:

If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate any person in any State, Territory, Commonwealth, Possession, or District in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or because of his having so exercised the same; . . . They shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than ten years, or both. . . .

Analysis

In this count, prosecutors allege that Trump and his co-conspirators engaged in a conspiracy designed to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” persons engaged in the enjoyment of their rights—namely the right to vote and to have votes counted properly.

Section 241 suffers from many of the same problems as other “conspiracy” laws, but it is a little bit clearer than most. So that’s nice.

If we put aside the general moral and legal problems with the whole notion of conspiracy as a standalone crime, certain conditions would need to be met to convict under this section:

- The intent must be to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate,” and

- There must be a nexus to “the free exercise or enjoyment” of a “right or privilege” secured by the U.S. Constitution or federal laws.

The right to vote is obviously a “right or privilege” secured by the U.S. Constitution, so the second point is covered . . . but the claim that Trump was trying to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” is largely baseless. The forty-five-page indictment only includes one instance of each of those words, and they are all in one sentence . . . the one that quotes section 241.

We must also grapple with the fact that Trump probably believed he won the 2020 election. If so, his efforts to pressure state officials to investigate alleged fraud, review and “correct” results, send alternate elector slates, and so-forth were not nefarious, just woefully misguided.

Conclusion

For the reasons described in the “Background” section under the subheading “On Conspiracy,” the “Conspiracy Against Rights” charge (count 4) is morally and constitutionally invalid. Trump should be acquitted.

Even if this were not the case, prosecutors have provided no evidence of any intent to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” anybody . . . and, even if they had, it would be difficult (if not impossible) to prove criminal intent beyond a reasonable doubt.

Summary of Conclusions

The following is a summary of conclusions on each of the charges comprising this federal indictment. If they go to trial, this is how they should turn out based on the analyses above:

- Count 1, “Conspiracy to Defraud the United States” – Not guilty. The charge is morally and constitutionally invalid.

- Even if the charge had been valid, prosecutors have not described anything that would constitute “fraud” under the statute, or any criminal offense the conspiracy intended to commit, so acquittal would still be appropriate.

- Count 2, “Conspiracy to Obstruct an Official Proceeding” – Not guilty. The charge is morally and constitutionally invalid.

- Even if the charge had been valid, Trump’s attempts to influence an official proceeding—the counting of the electoral votes—were not obstructive acts, and corrupt intent has not been proved, so acquittal would still be appropriate.

- Count 3, “Obstruction of, and Attempt to Obstruct, an Official Proceeding” – Not guilty. An attempt to influence an official proceeding is not an attempt to obstruct it, and prosecutors have not proved corrupt intent.

- Trump badly mismanaged the events of January 6, 2021, including the Capitol riot, but he did not incite anything, nor can he be held legally responsible for the effects the riot had on proceedings in Congress.

- Count 4, “Conspiracy Against Rights” – Not guilty. The charge is morally and constitutionally invalid.

- Even if the charge had been valid, there is no evidence that Trump had a criminal intent to “injure, oppress, threaten, or intimidate” anybody, so acquittal would still be appropriate.

These conclusions are based on the facts as I understand them today. New evidence could change them. If that happens, I will reevaluate the affected parts of this article and add notes in the “updates” section below to describe changes.

Updates

This post will be updated when new information becomes available. I will include editorial notes in this section briefly explaining any substantial changes.

Notes

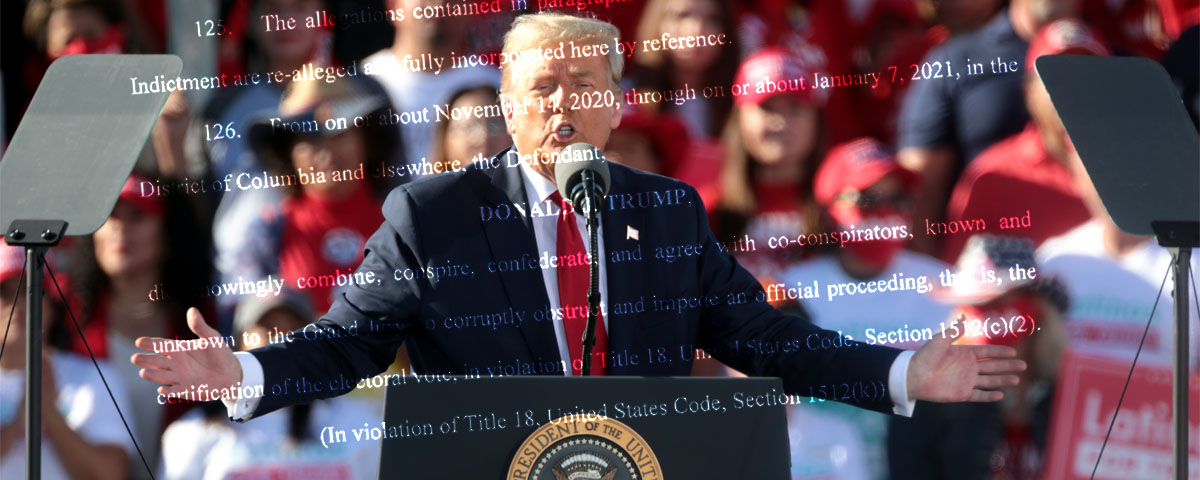

The feature graphic at the top of this article incorporates the photo listed below. It is licensed under a Creative Commons license:

The PDF of the indictment included near the beginning of this post has been processed with optical character recognition (OCR) software so its content can be selected and searched. It has also been optimized to reduce file size.

Works Consulted

- Batten, Donna, editor. Gale Encyclopedia of American Law. Third Edition. 14 Volumes. Detroit, MI: Gale, Cengage Learning, 2010. Gale eBooks (via Fairfax County Public Library).

- Garner, Bryan A., editor. Black’s Law Dictionary. Eleventh Edition. Saint Paul, MN: Thomson Reuters, 2019. Westlaw (via Loudoun County Public Library).

- Merriam-Webster Law Dictionary (M-W Law). Online Edition. Merriam-Webster Inc., 2024. Merriam-Webster.com.

- Sheppard, Stephen Michael. Wolters Kluwer Bouvier Law Dictionary. Desk Edition. 2 Volumes. CCH Inc., 2012. Nexis Uni (via Library of Virginia).

- USCA, Title 18, Part I. United States Code Annotated. Thomson Reuters, 2023. Westlaw (via Loudoun County Public Library).

- USCS, Title 18, Part I. United States Code Service. LexisNexis, 2023. Nexis Uni (via Library of Virginia).

Series Links

- Part 1: Brief Overview

- Part 2: Business Records Case (New York)

- Part 3: Documents Case (Federal)

- Part 4: Election Case (Federal) (this post)

- Part 5: Election Case (Georgia)

- Part 6: Conclusions